Discover Iran: Pasargadae, cradle of Persian architecture and world's first garden design

By Ivan Kesic

- As the first capital of the Achaemenid Empire, Pasargadae is the birthplace of a unique Persian architectural style, which brilliantly synthesized artistic and construction techniques from across the empire, including Ionian, Lydian, Egyptian, and Mesopotamian traditions.

- The site is globally significant for creating the prototype of the formal Four Gardens layout (Chaharbagh), a paradisiacal design that became a foundational model for garden design across the Islamic world and beyond.

- Pasargadae stands as an exceptional monument to the Achaemenid civilization's revolutionary principle of respecting cultural diversity, with its art and architecture serving as a physical testament to the world's first great multicultural empire.

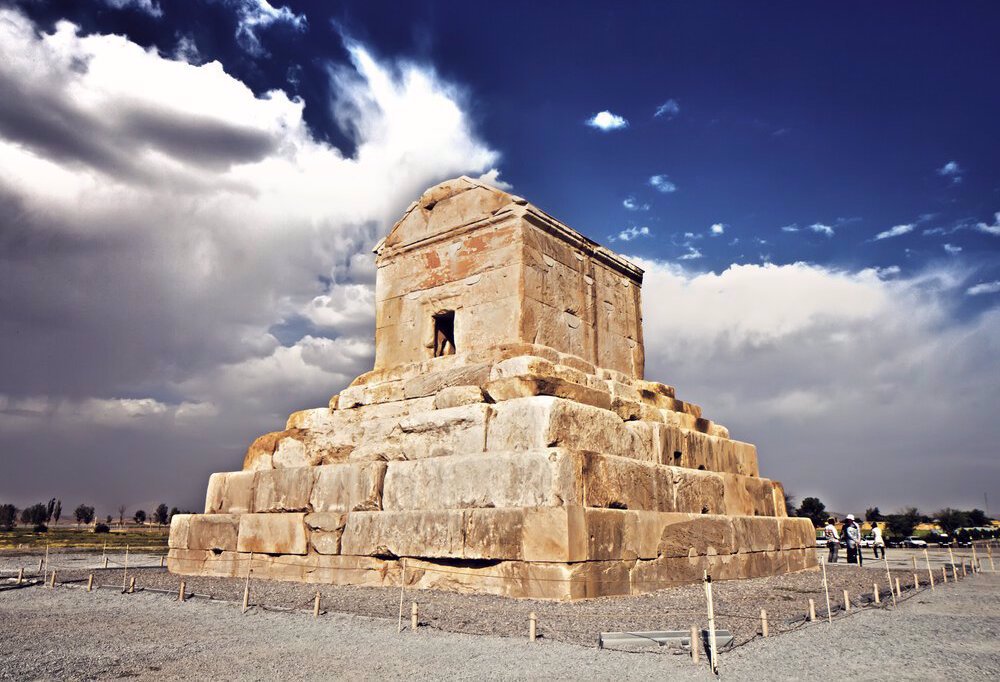

Rising from the vast, windswept Morghab plain in northern Fars province stands a collection of stone ruins whose quiet dignity belies their revolutionary place in human history.

This is Pasargadae, the first dynastic capital of the Achaemenid Empire, founded by the visionary Cyrus the Great in the 6th century BC as the ceremonial heart of the first great multicultural empire in Western Asia.

Its elegant, slender columns and serene gardens were planted in the homeland of the Persians, a deliberate statement of a new world order born from the fusion of countless conquered cultures.

The site’s most iconic sentinel, the timeless tomb of Cyrus himself, has watched over the plain for millennia, a stark and powerful silhouette against the mountain sky that has drawn pilgrims, travelers, and conquerors to its base.

More than just an ancient capital, Pasargadae represents a profound moment of architectural and philosophical genesis, the first outstanding expression of a uniquely Persian royal style that would find its full flowering in Persepolis.

The artistic and technological innovations pioneered here, from its synthetic artistry to its paradisiacal garden design, did not merely adorn a king's palace; they gave physical form to an ideology based on respect and inclusion, creating a prototype for Western Asian architecture and design whose influence would echo for centuries.

To walk among the ruins of Pasargadae is to walk through the birthplace of an idea—the concept of a multicultural empire—and to witness the very foundations of an Iranian civilization that would dominate the ancient world.

Synthesis of stone: the artistic and technological genius

The architectural landscape of Pasargadae stands as a breathtaking testament to the cosmopolitan vision of its founder, Cyrus the Great, who harnessed the finest skills and traditions of his vast dominion to create a new, imperial aesthetic.

At the heart of this innovation was a revolutionary adoption of advanced stone-working techniques, a deliberate departure from the mud-brick and wood constructions of earlier Persian kingdoms.

Cyrus’s architects and masons, likely drawn from the recently conquered lands of Lydia and Ionia, brought with them a mastery of stone that was unparalleled in the highlands of Persia, introducing sophisticated methods like anathyrosis joints for perfect stone fitting and the use of dove-tailed iron and lead clamps for seismic stability.

This technical prowess facilitated the creation of finely jointed stone platforms, soaring columns, and intricately carved doorways that would become the hallmark of Achaemenid architecture for centuries to come.

The very fabric of Pasargadae, from the massive ashlar blocks of the Tall-e Takht terrace to the delicate fluting on column bases, speaks of a technological leap that was as intentional as it was brilliant, transforming local building practice into a permanent, monumental language of power.

Yet this was not mere imitation; the genius of Pasargadae lies in its fearless and inventive synthesis, where imported techniques served a distinctly Persian artistic and ideological vision, creating something entirely new in the ancient world.

Iconography of power: sculpture and symbolism

This synthetic spirit is vividly embodied in the site's sculptural and decorative arts, which co-opted the visual traditions of conquered empires to forge a cohesive iconography for a new one.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the remains of Gate R, a freestanding propylaeum that is the first of its kind, where the very concept of a gateway was divorced from defensive walls to become a purely ceremonial and symbolic structure.

Within this grand hall, the doorways were once flanked by colossal winged bulls, human-headed lamassu directly inspired by the protective genii of Neo-Assyrian palaces, but their purpose was subtly transformed.

The most striking survivor is a majestic, three-meter-high winged figure carved on a door jamb, a figure that encapsulates the Pasargadae ethos.

It wears a Syro-Phoenician-style Egyptianizing crown, an Elamite robe adorned with Ionian rosettes, and is rendered with a Neo-Babylonian sensibility, all within the Assyrian tradition of protective spirits.

This figure was not a mere copy but a deliberate creation, an evocation of the empire's diverse peoples woven into a single, powerful image meant to conjure the protective power of the Achaemenid state itself.

Similarly, the columned halls of Palaces S and P, while based on an indigenous architectural form, were realized with a stunning innovation in their design and decoration.

The quintessentially Persian addorsed animal capitals—exquisitely carved bulls, lions, and a unique horse—were likely invented here, experiments in a form that would become a leitmotif of Persian grandeur.

The open, multi-axial plan of these palaces, with their porticoes in antis borrowed from Ionia, broke radically from the single-focus axis of traditional Near Eastern architecture, creating spaces that were fluid, welcoming, and designed to be appreciated within the context of sprawling, verdant gardens.

Invention of paradise: the fourfold garden

The most profound and enduring innovation at Pasargadae, however, was not in its stonework but in its landscaping—the creation of the royal garden, the first known example of the formal chaharbagh, or fourfold garden.

Archaeologists uncovered a network of stone water channels and basins that defined two adjoining rectangles, a layout that divided the garden into four precise quarters.

This design was almost certainly an architectural evocation of Cyrus’s Mesopotamian-derived title, "King of the Four Quarters," transforming the very earth into a symbol of his universal dominion.

The central location of a throne base in the "garden portico" of Palace P provided the king with an unobstructed vista down the central axis of this planted paradise, a place where he could hold court amid the beauty of a controlled nature.

This concept of the royal garden as a planted, watered, and symmetrically ordered paradise, a pairidaēza from which the word "paradise" itself is derived, became a fundamental prototype.

The Four Gardens design invented at Pasargadae would be replicated and refined, its influence flowing far beyond the bounds of the Near East to become a cornerstone of garden design in the Islamic world and beyond, making it one of Iran's most significant contributions to world culture.

At Pasargadae, art and technology were not separate pursuits; they were intertwined tools used to build not just a capital, but a new imperial identity, one that was as technologically sophisticated as it was artistically bold and philosophically profound.

Pasargadae as a singular beacon of world heritage

The significance of Pasargadae for world heritage transcends its age and its beauty, residing instead in its powerful testimony to a revolutionary approach to empire that respected the cultural diversity of its peoples, a principle given form in its very stones.

As the capital of an empire that stretched from the Eastern Mediterranean to the Indus River, Pasargadae stands as an exceptional witness to the first phase of the Achaemenid civilization, a polity consciously conceived as a multicultural enterprise where different traditions were not erased but integrated.

This respect for diversity, so starkly different from the brutal assimilation practices of earlier empires like Assyria, was the core of Achaemenid statecraft, and Pasargadae is its earliest and purest architectural expression.

The site’s outstanding universal value is recognized by UNESCO precisely for this reason, as it showcases the fundamental phase in the evolution of classic Persian art and architecture, a style born from the synthesis of Ionian, Lydian, Egyptian, Babylonian, and Elamite influences into a coherent and majestic new whole.

The enduring power of this synthesis is palpable, making the ruins not just a collection of ancient buildings but a permanent monument to the idea that strength can be found in unity and diversity, a concept as resonant today as it was in the 6th century BC.

Pasargadae’s foundational role in coexistence

What truly sets Pasargadae apart from its contemporaries and even its own successor, Persepolis, is its role as a pristine prototype, a canvas upon which the very grammar of Achaemenid art and architecture was first written.

While Persepolis is larger and more complete, it is the perfected and codified culmination of a style that was invented, tested, and refined at Pasargadae.

Every key element that would define Persian imperial construction for two centuries saw its first expression here: the freestanding columned hall, the monumental stone terrace, the finely crafted stone water channels of the royal garden, and the iconic tomb design that would influence later royal mausoleums.

The Tomb of Cyrus itself is a masterpiece of unique synthesis, its gabled-roof chamber derived from Anatolian tombs and its stepped plinth possibly echoing Mesopotamian ziggurats, yet the overall composition is without direct parallel, a serene and powerful statement of individuality and sanctity.

This spirit of prototype extends to the unfinished state of the Tall-e Takht terrace, whose raw, undressed stones poignantly capture a moment of ambitious construction frozen in time by Cyrus's death, offering archaeologists a rare glimpse into the very process of Achaemenid building.

Pasargadae is thus the foundational text, while Persepolis is the magnum opus, and the former’s value lies in its revolutionary, first-draft quality.

The authenticity of Pasargadae is profound and palpable, its location and setting on the Morghab plain largely unchanged over millennia, with the ruins standing amidst an agricultural landscape that continues the ancient rhythms of life.

There has been no modern reconstruction at the site; the remains of all the monuments, from the tomb to the palace foundations, are authentic, and recent restoration work has scrupulously utilized traditional technology and materials.

This authenticity allows the visitor to connect directly with the world of Cyrus, to feel the same winds and see the same mountains that shaped the vision of the empire's founders.

The site’s integrity is safeguarded within its boundaries, which contain all the key elements needed to convey its universal value, though it faces pressures from agriculture, potential village growth, and the relentless natural elements.

Pasargadae is more than an Iranian treasure; it is a landmark in human history that speaks to the possibility of a unified world built on mutual respect, a legacy carved in stone and etched into the landscape, reminding all of humanity of a time when a ruler chose to build his paradise not on the subjugation of cultures, but on their harmonious and brilliant integration.

Nouri al-Maliki defends Hashd al-Shaabi as inseparable part of Iraqi security system

British PM Keir Starmer faces calls to resign

Iran’s Kowsar satellite beams Islamic Revolution anniversary message across region

VIDEO | Press TV's news headlines

VIDEO | Indian regions celebrate Iran’s Islamic Revolution anniversary

Iran’s missile program will never be on negotiating table: Shamkhani

Hezbollah: 47 years of Iranian progress proof of ‘abject failure’ of Western plots

Iran’s Larijani meets Qatari emir amid nuclear talks with US

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website