Discover Iran: Persepolis, a masterpiece of Persian engineering, architecture in Fars

By Ivan Kesic

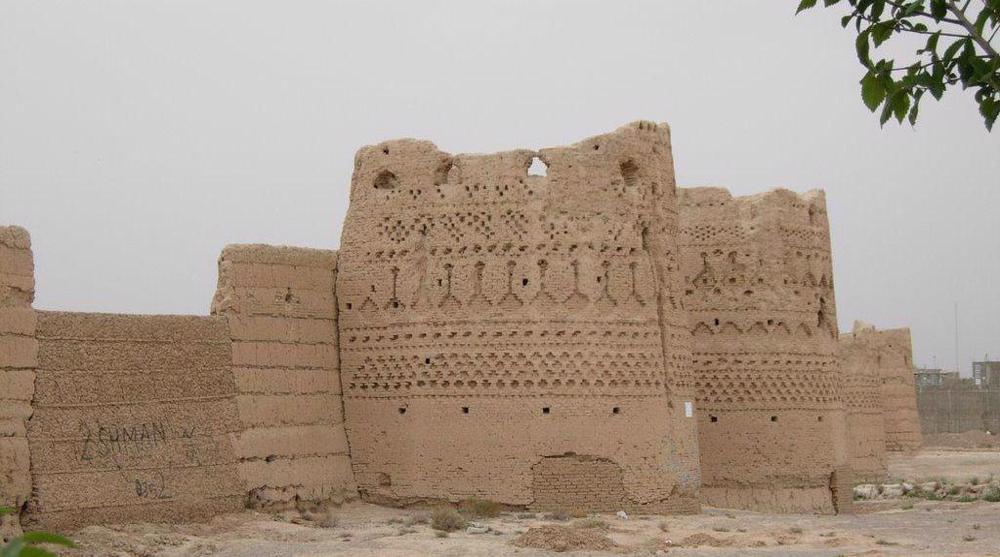

Rising from the Marvdasht plain at the foot of the Kuh-e Rahmat, or Mountain of Mercy, the majestic ruins of Persepolis stand as a silent testament to the pinnacle of Achaemenid Iranian power and artistry.

Founded by Darius I the Great around 518 BCE, this was not merely a city but a monumental ceremonial capital, an awe-inspiring complex constructed on an immense half-artificial, half-natural terrace designed to project the absolute authority and divine-sanctioned rule.

Known in its heyday as Parsa, the heart of the Persian homeland, the site was conceived as a grand stage for imperial receptions and festivals, a place where the vastness and diversity of the empire could be ritually acknowledged and displayed.

Its importance and unparalleled quality place it among the world's greatest archaeological sites, a unique gem of Achaemenid architecture, urban planning, and art that has no equivalent.

The sprawling terrace, with its majestic stairways, colossal gateways, and towering columned halls, continues to embody, just as Darius intended, the very image of the Achaemenid monarchy itself.

To walk through its ruins is to traverse a landscape where stone was carved into a permanent narrative of power, piety, and multicultural synthesis, a legacy that continues to captivate and inspire the world centuries after Alexander’s fateful fire sought to consign it to oblivion.

Architectural marvel of engineering and synthesis

The very foundation of Persepolis was a breathtaking feat of engineering, a deliberate act of shaping nature to serve a grand imperial vision.

The creation of the vast 125,000-square-meter terrace required leveling a rocky promontory, filling depressions with earth and rubble, and constructing retaining walls of enormous, finely joined stone slabs that rose twelve meters above the ground.

This was not a haphazard foundation but a meticulously planned base, equipped with a sophisticated and flawlessly functioning system of underground water channels, drains, and deep wells designed to manage rainfall and provide for the complex, a system that still performs its intended function today.

The architectural genius of Persepolis is most profoundly expressed in its revolutionary use of the column, where Achaemenid engineers and architects achieved a stunning harmony of strength and elegance.

By carefully engineering lighter roofs and utilizing wooden lintels, they were able to employ a minimum number of astonishingly slender columns, some just 1.6 meters in diameter yet soaring to heights of nearly 20 meters, creating vast, open, and airy spaces that dwarfed visitors.

These columns were crowned by the most iconic of Achaemenid creations: elaborate double-bull or double-lion capitals, where the forequarters of two kneeling beasts, placed back-to-back, extended their coupled necks and twin heads to directly support the massive cedar beams of the ceiling.

This was not an isolated innovation but part of a conscious and brilliant synthesis, where the Persians acted as master planners who directed artisans from across their empire—drawing on Lydian and Ionian stone-working techniques, Assyrian protective motifs, Egyptian decorative elements, and Babylonian artistic traditions—to forge a coherent and majestic new Imperial style that was, in its final expression, uniquely and magnificently Iranian.

Stone chronicle of an empire: art and iconography

Beyond its structural grandeur, Persepolis was designed as a vast stone canvas, its walls and stairways covered in sculpted friezes that narrated the ideology and stability of the empire in a universal language of imagery.

The most splendid of these stone chronicles adorn the double-reversed stairways of the Apadana, or Audience Palace, where the facade is divided into a breathtaking panorama of imperial harmony.

One wing showcases three superimposed registers of the empire’s military and aristocratic elite: immaculately detailed ranks of Persian and Median guards, staff-bearers, and dignitaries, the latter often shown holding hands or touching shoulders as they proceed with relaxed and cheerful demeanors, capturing a rare and humanizing glimpse of ancient courtly life.

The corresponding wing presents a vibrant procession of twenty-three gift-bearing delegations from every corner of the empire, each meticulously rendered in their distinct national dress and accompanied by their unique tributes—from the Bactrians leading a two-humped camel and the Lydians presenting ornate vases to the Ethiopians offering an elephant tusk and the Scythians bringing bridled stallions.

A Persian or Median usher gently holds the hand of each delegation leader, a gesture of cordiality and guidance that symbolizes the empire’s unifying, albeit authoritative, embrace of its diverse subjects.

This entire ceremonial procession leads toward a central scene, now blank but originally occupied by the magnificent "Treasury Reliefs," which depicted the king enthroned under a baldachin, receiving this global homage.

The symbolism is reinforced by recurring motifs like the lion goring a bull, likely representing the cyclical nature of time and royal power, and the majestic winged discs and human figures that hover above the king, symbolizing the divine Royal Glory, or xvarenah, bestowed upon him by Ahura Mazda.

Every sculpture was originally ablaze with color—vibrant reds, blues, and golds—and inlaid with precious metals, transforming the stone narratives into a dazzling and polychrome testament to the empire's wealth and cosmic order.

Ceremonial heart: palaces of power and pageantry

The terrace of Persepolis was a carefully orchestrated landscape of power, with each building serving a distinct ceremonial function in the ritual theater of the empire.

The journey for a visitor began at the monumental "Gate of All Lands," a colossal square hall commissioned by Xerxes and flanked by enormous carved winged bulls, whose trilingual inscription announced its purpose as a welcoming point for the peoples of all nations.

From here, one would proceed to the heart of the complex: the Apadana of Darius and Xerxes. This was the largest and most imposing palace, a towering structure with a central hall supported by 36 slender columns, capable of accommodating 10,000 guests for vast royal audiences.

Its northern and eastern porticoes, accessed by the famous sculptured stairways, served as the primary stages for the ceremonial events depicted in their friezes.

Deeper within the complex stood other architectural marvels, like the Tachara, or Palace of Darius, the oldest structure on the terrace, which served as a model for later palaces and for the facades of the royal tombs at nearby Naqsh-e Rostam.

Further on, the Tripylon, or Central Palace, acted as a crucial link between the major buildings, its sculptures showing the king and crown prince being carried on a throne upheld by representatives of subject nations.

The scale culminated in the Throne Hall, or Hundred-Column Hall, begun by Xerxes and completed by Artaxerxes I, a cavernous space that was the second-largest palace, its forest of columns creating an atmosphere of overwhelming grandeur intended for more intimate royal receptions.

This intricate arrangement of palaces, gateways, and courtyards was not a chaotic agglomeration but a unified and symbolic architectural plan, where the very movement through the space was a ritual reinforcing the hierarchy and eternal strength of the Achaemenid throne.

Legacy and significance as world heritage

Persepolis holds an undeniable and profound significance for world heritage, recognized by UNESCO as a site that bears a unique witness to the most ancient civilization.

Its value lies not only in its breathtaking scale and artistry but in its powerful testimony to the Achaemenid Empire's revolutionary model of statecraft—a vast, multicultural entity that respected the diversity of its peoples, a principle physically embodied in the synthetic art and architecture of its ceremonial capital.

The site is authentic in the truest sense; its location, setting, and materials are original, with restoration work carefully utilizing traditional technology and no modern reconstructions cluttering the ancient remains.

The integrity of the property is protected within its boundaries, which contain all the key elements needed to convey its universal value, from the Apadana and the Treasury to the royal tombs carved into the adjacent hillside.

The ongoing work of the Persepolis researchers, guided by a dedicated management plan and supported by national and international expertise, is crucial to monitoring pollutants, preventing vandalism, and ensuring that this irreplaceable link to humanity's shared past endures.

Persepolis is both an Iranian treasure and a global landmark, a monumental expression of a pivotal moment in human history when an empire chose to build its legacy in stone, creating an architectural poem whose verses continue to speak of power, unity, and sublime artistic achievement.

Switzerland weighs European option as Patriot delivery stalls

VIDEO | Press TV's news headlines

VIDEO | Another Gaza medic dies in Israeli custody

VIDEO | Hezbollah says prepared to defend Lebanon, does not seek war

VIDEO | Celebrations held across China to welcome New Year

VIDEO | Mexico’s historic battle reenactment draws over 200,000 visitors

'ICE-style enforcement': nearly 70 groups slam EU migration policy

Araghchi holds key meetings in Geneva ahead of indirect Talks with US

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website