Discover Iran: A timeless journey through the enchanting alleys of Astarabad, Gorgan’s old city

By Ivan Kesic

- The old city center is a remarkably resilient, still-inhabited urban palimpsest, rare among Iranian historical fabrics, whose organic layout, hierarchical alley network, and distinctive inward-facing houses with windcatchers (badgirs) represent a sophisticated vernacular adaptation to the Caspian region's moderate, humid climate.

- Rising from the shadow of the ancient metropolis of Gorgan after its destruction by Mongols and earthquakes, Astarabad evolved into a strategic frontier stronghold and political cradle, ultimately serving as the familial capital (dar al-molk) of the Qajar tribe.

- The city's enduring architectural identity was forged at the confluence of turbulent history and precise environmental response, with its formidable walls and gates bearing witness to successive conflicts and repairs.

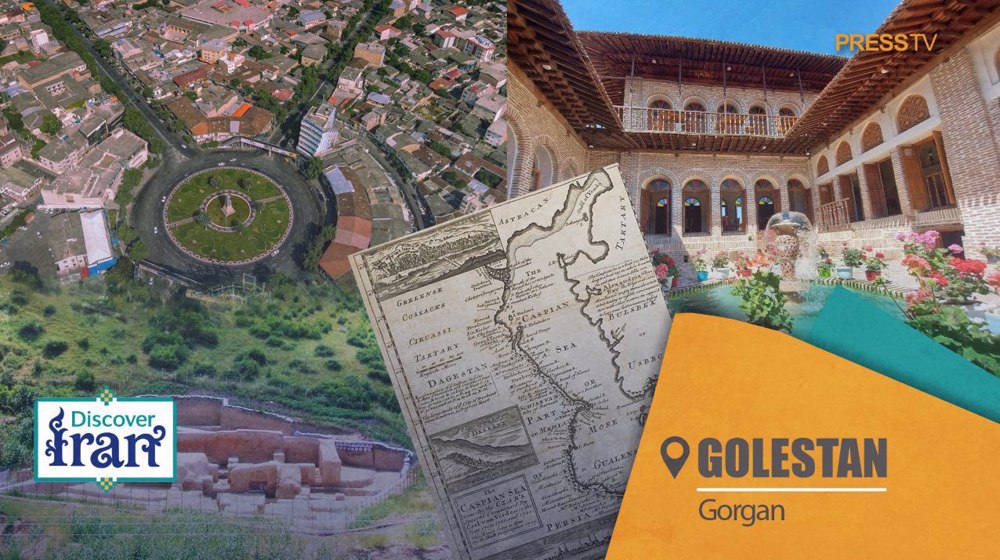

At the heart of modern Gorgan city in northeastern Golestan province, beneath the bustling expansion of a provincial capital, lies one of Iran’s most historically significant and resilient urban fabrics: the old city center, known for centuries as ‘Astarabad’.

The old city of Astarabad, now known as Gorgan, represents not a frozen relic but a continuously evolving entity, whose architectural patterns – from its defensive walls and hierarchical alleyways to its inward-facing houses with distinctive windcatchers – offer profound insights into the adaptation of urban life in the southeastern Caspian region across the Islamic era, particularly through the transformative periods of Safavid and Qajar rule.

Historical and geographical crucible

The architectural identity of old Astarabad city is inextricably linked to its unique geographical and historical context.

Situated on the southeastern fringe of the Caspian Sea, the city occupies a transitional zone between the semi-tropical humidity of western Mazandaran province and the arid steppes of Turkmenistan to the northeast.

This position, bounded by the majestic Alborz Mountains to the south and the Gorgan River to the north, endowed it with a moderate climate while also making it a perpetual frontier, vulnerable to incursions and a strategic prize for competing powers.

Historically, Astarabad emerged from the shadow of the ancient metropolis of Gorgan (Jurjan), 70 kilometers to the northeast near the modern city of Gonbad-e Kavus, which was devastated by the Mongols and a catastrophic earthquake in the 12th century.

The subsequent migration and refocus of urban life led to the ascendance of Astarabad, which by the early Islamic period was noted by geographers like Maqdisi as a thriving center for silk weaving.

Its significance was cemented when it became the familial stronghold and dar al-molk (seat of power) for the Qajar tribe, eventually giving birth to Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar, the founder of the Qajar dynasty that ruled over Iran from 1789 to 1925.

This turbulent history of resilience – through Arab conquests, Buyid-Ziyarid conflicts, Mongol disruptions, Timurid intrigues, and Safavid-Uzbek wars – is physically imprinted upon its urban form, where each phase of destruction and reconstruction added a layer to its architectural narrative.

Urban morphology: Walls, gates, and the organic neighborhood system

The foundational structure of old Astarabad city was defined by a robust, inward-facing urban fabric enclosed within formidable defensive works.

The city was encircled by a mud-brick wall, approximately 5-6 kilometers in perimeter, reinforced with towers and protected by a deep moat.

This fortification, repeatedly damaged in wars and conflicts and repaired by figures from Shah Rukh Timurid to Nader Shah and Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar, served as both a physical and symbolic boundary.

Five major gates punctuated this wall, each acting as a nexus for trade and travel, thereby dictating the city’s growth vectors: the Bastam Gate (east, towards Khorasan), the Sabzeh Mashhad or Fojjard Gate (north, towards old Gorgan), the Chehel Dokhtaran Gate (south, to the mountains), the Mazandaran Gate (west), and the Dankoban Gate.

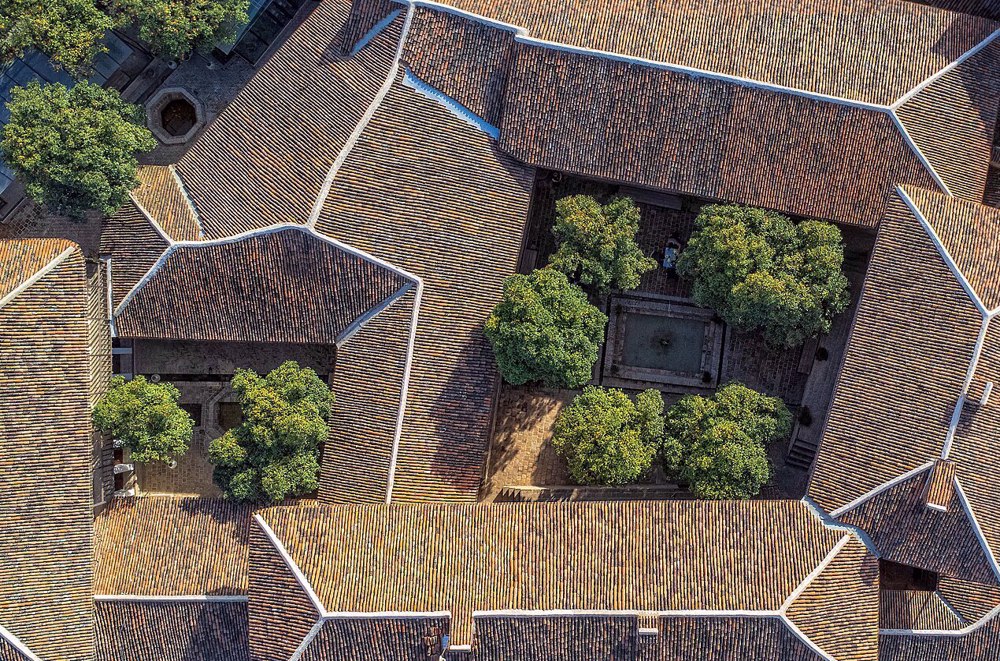

The urban tissue within was not a planned grid but an organic accretion of residential neighborhoods (mahallehs) around vital nuclei.

Three primary mahallehs – Nalbandan in the east, Meydan in the west, and Sabzeh Mashhad in the north – formed the core, each further subdivided into smaller, named quarters like Sarcheshmeh, Dushanbe, or Baghshah.

This neighborhood structure was largely autonomous, with each unit typically containing its own mosque, bathhouse (hammam), water reservoir (ab anbar), and sometimes a school (madrasa) or tekyeh, creating self-sufficient cellular communities within the whole.

Hierarchical circulation network and hydraulic adaptations

The communication network within Astarabad’s old fabric was a direct reflection of its social and environmental logic, organized in a clear hierarchy from public to private realms.

Main arteries, often 4-7 meters wide, formed the primary skeleton, connecting the city gates and major public nodes like the central bazaars and the Grand Mosque.

These roads frequently followed the ancient routes of irrigation canals and water supply networks from the Ziarat River and local qanats, underscoring the symbiosis between urban movement and water management.

Secondary lanes, narrower at 3-5 meters, branched off these main routes, weaving through the mahallehs and providing access to residential clusters.

The most private level consisted of dead-end alleys (kucheh-ye boni), often only 1-3 meters wide and sometimes gated, serving a handful of households and offering a protected, communal semi-public space.

This labyrinthine system, with its deliberate twists and turns, was not arbitrary; it was ingeniously adapted to the micro-climate, designed to channel cooling northern breezes while providing shade, and to manage the flow of both people and precious water, with surface runnels often bisecting the alleys for drainage.

Climatic resonance in domestic architecture

The residential architecture of Astarabad stands as a master class in vernacular adaptation to the Caspian region’s humid, moderate climate.

Houses were predominantly inward-looking, organized around central courtyards that provided light, ventilation, and private outdoor space.

The primary building volumes were typically oriented on an east-west axis, with the main living spaces (seh-dari, panj-dari rooms) facing north and south to capture optimal sunlight and beneficial winds.

A defining feature of the Astarabad skyline, especially among more affluent homes, was the badgir (windcatcher), a tower-like structure that captured cooler, higher-altitude breezes and funneled them into the interior living spaces.

Roofs were gently sloped and covered with clay, supported by robust wooden trusses that often extended considerably beyond the walls to form protective eaves against rain.

Construction materials were resolutely local: baked and mud brick, wood from the Alborz forests, and clay plaster.

The exteriors, while largely austere, could feature decorative brickwork or inscribed plaster bands (epigraphy) with Quranic verses or poetry, while the interior focus was on spacious, high-ceilinged rooms with intricate wooden porches (ayvan), shelves (taqcheh), and in wealthier examples, detailed stucco molding (gach-bori).

Socio-economic stratification in the built fabric

The old city’s architectural landscape clearly articulated the socio-economic stratification of its inhabitants. The dwellings of the aristocracy, gentry, and prosperous merchants were substantial compounds.

These were often two-story structures with enclosed courtyards lush with citrus trees, featuring large, separate rooms connected by decorated wooden verandas.

The rooms boasted built-in niches and closets, and the shahneshin (main reception room) often displayed the family’s wealth through elaborate decorations. Cellars (zir-zamin) dug deep beneath the house provided natural refrigeration.

In stark contrast, the houses of the middle and lower classes were far more modest. These were typically single-story structures with smaller courtyards paved with river stones, fewer rooms (2-3), and minimal ornamentation.

The roofs were thatched or clay-covered on simpler wooden beams, and the construction primarily utilized raw mud.

Despite these differences, both typologies shared the core principles of inward orientation, climatic responsiveness, and organization around a service core that included a kitchen, storage, and a water cistern in the courtyard.

Monuments of piety and power: the public architecture

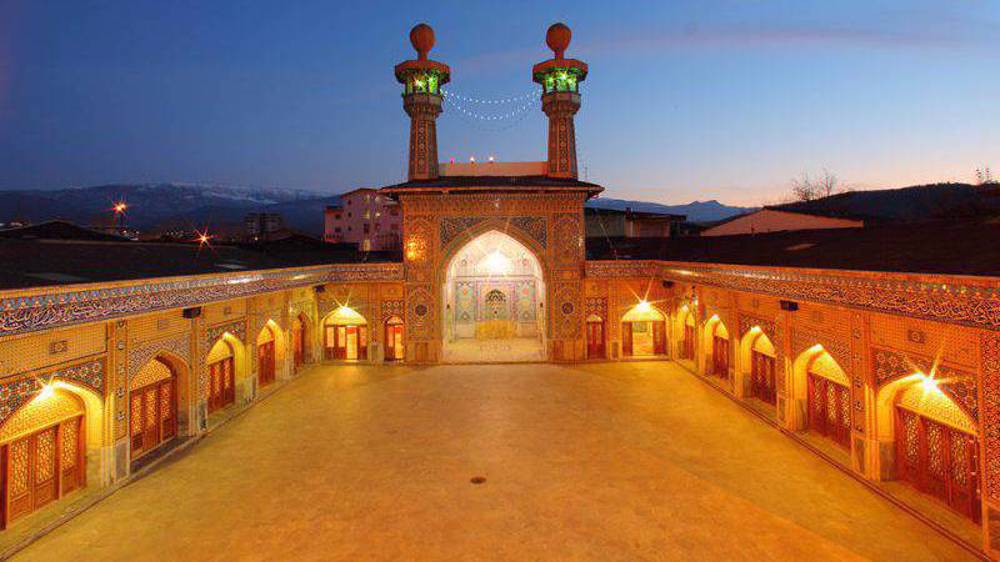

While the residential fabric formed the body of the city, its public monuments articulated its spiritual and political heart. The most significant surviving historic structure is the main mosque (Masjed-e Jameh), whose origins likely date back to the early Islamic period.

Its most venerable element is a free-standing brick minaret, with patterning and Kufic inscriptions suggesting a 12th-century Seljuk provenance.

The mosque itself, however, bears the marks of continual renewal, with inscriptions documenting reconstructions under the Safavid Shah Abbas I and later under Nader Shah Afshar, reflecting its enduring central role.

Another key monument is the Imamzadeh Nur, a polygonal baked-brick tomb tower believed to house a descendant of Imam Musa al-Kazim, the seventh Shia Imam.

Although undated, its architectural style and a magnificent cut-plaster mihrab point to a possible late Seljuk or Ilkhanid foundation, with exquisite wooden doors added in the 15th century.

As noted by early 20th-century Western observers, the city was historically dense with places of worship – mosques, tekyehs, and shrines – justifying its Qajar-era epithet Dar al-Mo’menin (Abode of the Faithful).

These monuments, alongside the now-vanished citadel and the bustling bazaars attached to the main gates, formed a network of public nodes that gave structure and meaning to the surrounding organic residential growth.

Old fabric in the modern age: preservation and continuity

The old texture of Astarabad, now central Gorgan, presents a rare case of continuous habitation and organic evolution. Unlike many historic Iranian cores that have been abandoned or fossilized, it remains a living, dynamic urban center.

This very vitality, however, brings the threat of insensitive development and decay. Recognizing its immense value, the old fabric was registered as a National Monument (No. 41) as early as 1931.

Contemporary preservation efforts, spearheaded by entities like the Gorgan Old Fabric Cultural Heritage Base, focus on delineating the historic area, enforcing construction guidelines, and revitalizing its urban vitality without erasing its character.

The challenge lies in balancing the need for modern infrastructure with the preservation of the delicate scale, architectural integrity, and social patterns of the historic neighborhoods.

The enduring presence of the hierarchical alley network, the occasional surviving badgir punctuating the roofscape, and the active life within the old bazaars testify to a remarkable resilience.

The old city of Astarabad is not merely a relic to be studied; it is an ongoing dialogue between its layered past and its living present, offering an unparalleled educational resource on the vernacular urbanism of Iran’s Caspian region—a testament to how architecture and urban form can embody history, climate, and community across centuries.

US military deployment near Venezuela ‘dangerous precedent’: Pezeshkian

Pezeshkian heads to Central Asia for Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan visit

VIDEO | Press TV's news headlines

Iran protests to FIFA over provocative armband plan at soccer match in US

Discover Iran: A timeless journey through the enchanting alleys of Astarabad, Gorgan’s old city

VIDEO | Cambodians flee border towns as Thai-Cambodia clash enters third day

Leaked emails reveal Epstein’s central role in pro-Israel causes in US

Iran says expanding cooperation with China, Saudi Arabia in multiple fields

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website