#IR46: How Iran industrialized and modernized construction sector with domestic expertise

By Ivan Kesic

Since the Islamic Revolution of 1979 led by Imam Khomeini, one of Iran’s most remarkable transformations has been its self-sufficiency in the construction sector, a leap that has drastically improved living conditions across the country.

While Iran’s pre-revolution reliance on the West – especially the United States – for energy and military technology is well known, foreign monopolies also dominated critical industries such as construction.

In the first half of the 20th century, Iran’s technological underdevelopment necessitated cooperation with foreign powers for the building of roads, railways, bridges, dams, and modern infrastructure.

Nearly all major construction projects were conceived, designed, and executed by foreign firms, with minimal indigenous Iranian involvement. The dependence on outsiders was overwhelming.

By the 1960s and 1970s, American influence over Iran’s housing and construction industries had become a full-fledged monopoly, a result of the West-backed Pahlavi regime’s series of lopsided decisions that heavily favored American corporations.

The Cold War had already entrenched Iran as a dependent ally of Washington, with the ruling monarchy relying on American military and financial support.

But when oil prices skyrocketed, flooding Tehran with newfound wealth, the U.S. saw an opportunity to ensure that Iran’s massive revenues flowed right back into American pockets.

The Shah, fearful of both a Soviet invasion and a potential Communist-led uprising among peasants and workers, sought to build an overwhelmingly powerful military. He turned to Washington for cutting-edge weapons, equipment, and military infrastructure.

Seeing a golden opportunity, the Kennedy administration approved these lucrative arms deals—amounting to tens of billions of dollars, but with strings attached.

Under the guise of "internal reforms," the US pushed Iran to adopt policies aimed at reshaping its rural and working-class societies, eliminating potential threats to the monarchy, and securing Tehran’s unwavering allegiance to the Western bloc during the Cold War.

This included so-called economic "reforms" designed to steer Iran toward a free-market system, effectively opening the floodgates for American corporate domination in nearly all industries.

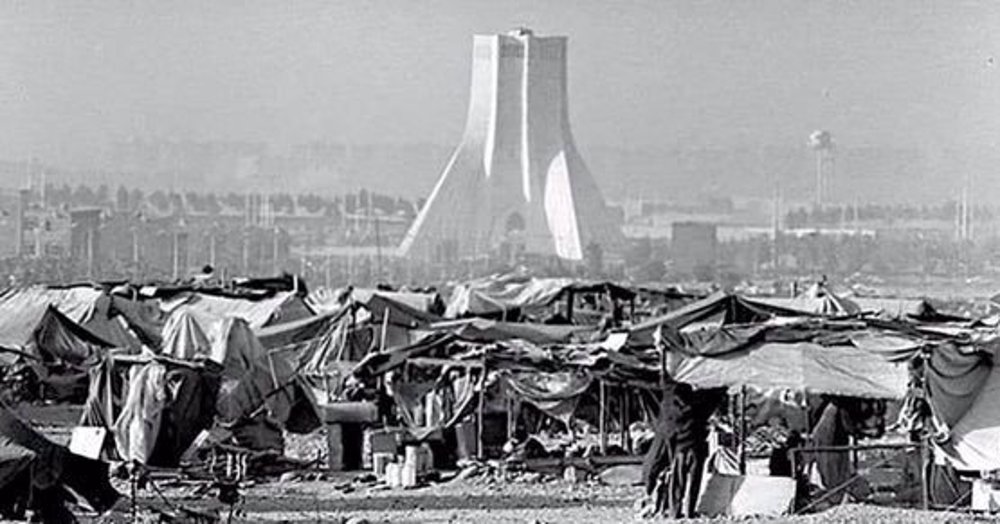

The land reforms implemented under this US-driven agenda proved disastrous. Over half of Iran’s peasant population remained landless, leading to mass migration into urban centers.

This rapid, unplanned urbanization only deepened economic inequalities and social unrest, sowing the seeds of future discontent – discontent that would ultimately contribute to the Revolution that broke Iran free from foreign strangleholds.

From foreign exploitation to national revival

The West-backed Pahlavi regime saw its housing crisis not as a problem to solve for the people but as an opportunity to industrialize and modernize construction, while simultaneously enriching itself and foreign corporations that had identified Iran as a gold mine for profit.

As international developers, construction giants, and architectural firms poured into Tehran, they pitched colossal and costly housing projects to the authorities.

At the same time, with ambitions growing unchecked, the Pahlavi regime welcomed oil behemoths like Exxon and Shell, granting them further control over Iran’s petroleum infrastructure, extraction, and export. This move only deepened the foreign stranglehold on Iran’s energy sector.

In the construction industry, absolute monopoly was handed to the American Starrett Housing Corporation, renowned for building the Empire State Building and Trump Tower in New York.

Thanks to its close ties with the Pahlavi Foundation, Starrett was granted exclusive control over Iran’s largest residential megaprojects of the 1970s, including the Ekbatan, Zomorod, and Alborz housing complexes in Tehran.

The Pahlavi regime generously provided Starrett with free nationalized land across the capital, allowing the corporation to make massive profits by selling thousands of apartments, primarily to the Iranian middle and upper classes, as well as to foreign buyers.

But the arrangement was even more lopsided: the contract required that over 80 percent of construction materials be imported from the United States, often at inflated prices many times higher than domestic alternatives.

Despite enjoying near-total control, free land, and guaranteed sales, Starrett consistently failed to meet deadlines and left projects unfinished.

The Ekbatan complex in western Tehran, for example, was never completed as planned. In another blow, the corporation found itself unable to sell units in the Zomorod complex, as many of its expected buyers – regime officers and foreign elites—fled the country after the Islamic Revolution.

With the revolution came an abrupt end to Starrett’s dominance. As US sanctions made further business impossible, the corporation arrogantly sued Iran years later, demanding compensation for its failed ventures – despite the fortune it had already extracted from the country.

The post-revolution period exposed the deep fragility of the overthrown unpopular regime, which had built its so-called "power" entirely on foreign dependency.

Suddenly, without American assistance, Iran faced difficulties servicing its imported fighter jets, operating foreign-built factories, or even completing its own housing projects.

Recognizing the urgency of self-sufficiency, the new leadership pivoted toward domestic production, local materials, and an emphasis on housing for the oppressed classes. After the Imposed War in the 1980s, the government launched sweeping initiatives to rebuild and expand the housing sector:

- Easy loan programs for affordable homeownership

- Government-controlled pricing for essential construction materials

- Massive land distribution at low prices

- Encouragement of housing cooperatives to empower ordinary citizens

What had once been a playground for foreign monopolies transformed into a national movement for self-reliance and equitable development, ensuring that Iran’s future would no longer be dictated by outside powers.

From dependency to global leadership

The sweeping reforms in Iran’s housing sector not only lowered costs but transformed urban landscapes, expanding cities horizontally, increasing per capita housing, and significantly reducing population density in residential areas.

With domestic expertise taking the lead, Iranian companies completed previously foreign-led megaprojects, including the Ekbatan, Lavizan, Omid, Apadana, and Atisaz complexes in Tehran, while also launching a wave of ambitious new developments.

The rapid expansion of the construction industry over the past four decades has completely reshaped Iran, making it unrecognizable compared to its pre-Islamic Revolution state.

In 1979, Iran was still largely rural, with the majority of its people living outside cities. Today, Iran’s urban population has skyrocketed from 48 percent to 77 percent, a full 20 percent higher than the global average.

This transformation was driven by infrastructure development, industrialization, and population growth, leading to the official recognition of nearly a thousand new cities – from just 373 before the revolution to over 1,300 today.

Building materials and construction methods underwent equally dramatic changes. Before the 1979 revolution, less than a quarter of homes were built with durable materials like steel and concrete, while two-thirds relied on fragile materials such as mud bricks, wood, and straw.

Despite the challenges of the Imposed War, the first few years after the revolution doubled the share of durable housing and cut the use of non-durable materials in half.

The momentum only accelerated: between 1990 and 2010, the percentage of unreinforced masonry buildings plummeted from 90 percent to just 23 percent, while steel and concrete structures surged from 3 percent to 74 percent.

By the time of the 2011 Iranian census, Iran boasted 20 million housing units—with a staggering 90 percent built after the revolution, compared to the mere 10 percent under the overthrown regime.

This transformation was fueled by Iran’s leap from construction material dependency to self-sufficiency and global prominence. In the pre-revolution period, Iran was producing a mere 5 million tons of cement and 500,000 tons of steel per year, leaving it heavily reliant on imports.

Today, Iran stands as an industrial powerhouse, manufacturing 65 million tons of cement and 31 million tons of steel annually, ranking 6th and 10th in the world, respectively. Not only does Iran meet its domestic needs, but it has become a major exporter of these critical materials.

Beyond structural materials, Iran has also become the third-largest producer of decorative and construction stones—trailing only China and India—with its exquisite stonework now a defining feature of modern Iranian architecture.

From an era of foreign monopolies and dependence to one of self-sufficiency and international leadership, Iran’s construction revolution stands as one of the greatest transformations of the post-revolution period.

Iran pursuing broader cooperation with African nations: Pezeshkian

Israeli minister threatens to seize entire Gaza if Hamas refuses to disarm

VIDEO | Gaza teacher starts ‘Little Wings’ initiative to bring joy to kids

Spanish FM urges firmer EU stance on Gaza crisis, West Bank settlement expansion

Israel ‘serious obstacle’ to nuke-free West Asia: Iranian diplomat

High-profile Israeli-American brothers on trial for sex trafficking and assault

Settlers served lavish lunch in Israeli prison holding fasting Palestinians

VIDEO | Press TV's news headlines

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website