#IR46: How Iran developed and mastered bioastronautical and human space program

By Ivan Kesic

Iran's space program has been steadily progressing, not only with the frequent launch of communications and observation satellites but also through its ambitious human spaceflight initiative, which aims to send its first astronaut into space by the end of this decade.

The progress in the space program since the 1979 Islamic Revolution has been described by experts as phenomenal despite illegal sanctions and embargoes imposed on Iran by Western powers.

It was a leap of faith for highly motivated Iranian scientists and took them several years following the 1979 revolution to put the country in space, joining a league of advanced nations.

In the late 2000s, Iran achieved a historic milestone by joining the exclusive group of just nine nations capable of independently launching objects into space.

This breakthrough came on February 4, 2008, when the Kavoshgar test rocket marked Iran’s first recorded reach beyond the boundary of outer space. Just months later, on August 16, the country took another bold step by launching a mock-up satellite into orbit aboard the Safir-1 carrier rocket.

Then, on February 2, 2009, the Islamic Republic of Iran cemented its place in the global space arena with the launch of Omid (Hope), its first operational satellite.

This cubic satellite, designed for research and telecommunications, orbited Earth for three months, demonstrating Iran’s growing capabilities in satellite technology.

Since that pioneering moment, Iran has continued to expand its presence in space, successfully developing and deploying five additional types of carrier rockets, which have propelled numerous communication, observation, and research satellites into orbit.

What makes Iran’s achievements even more remarkable is that it has built its space and rocket technology independently – despite facing relentless and unjust US sanctions that have hindered international collaboration in the scientific field.

While many other nations relied on foreign assistance to launch their space programs and other such initiatives, Iran charted its own course, proving its resilience and scientific ingenuity.

Beyond its satellite missions, Iran’s advancements in bioastronautics have been equally impressive, laying the groundwork for future human spaceflight and solidifying its position as a rising space power.

Sixth nation to send animals into space

Alongside its pioneering satellite launch program, Iran has been advancing a bioastronautical initiative, paving the way for future human space missions by first sending animals beyond Earth’s atmosphere.

The Life in Space Research Group at the Aerospace Research Institute (ARI) has been at the forefront of this effort since 2002, following a high-level decision that Iran should aim for human spaceflight.

To bring this vision to life, ARI partnered with the Iran Aerospace Industries Organization (IAIO) under the Ministry of Defence and Armed Forces Logistics (MODAFL) to develop specialized biocapsules capable of carrying living organisms into space.

The program’s early steps began in November 2006, with the launch of the Kavoshgar-A (Explorer-A) test rocket, reaching an altitude of 10 kilometers and carrying instruments to gather essential data.

Building on this success, Iran conducted another atmospheric flight on November 26, 2008, this time testing an empty biocapsule at an altitude of 40 km.

This mission utilized the Kavoshgar-B rocket, an upgraded version derived from the Nazeat-6H solid-fueled short-range ballistic missile, boasting a payload capacity of 130 kg.

Then, on February 3, 2010, Iran took a bold step forward, launching a Kavoshgar-B rocket equipped with a biocapsule containing a rodent, two turtles, and several worms.

This historic mission propelled its living cargo to an altitude of 55 km, marking Iran’s official entry into the select group of nations capable of sending animals into space.

Each of these milestones has brought Iran closer to its ultimate goal – human spaceflight – while also expanding the nation's expertise in space biology and life sciences beyond Earth's atmosphere.

Pioneering space biology

Iran’s bioastronautical program took a crucial step forward by sending ectothermic (cold-blooded) organisms into space, allowing scientists to study how these creatures adapt to microgravity and extreme thermal environments. These missions provided invaluable data through live footage and telemetry, transforming the biocapsule into a miniature environmental lab for further research.

Building on these successes, Iran set its sights on an even greater challenge: sending a mammal beyond the Kármán line—100 kilometers above Earth's surface—using more powerful carrier rockets.

On March 15, 2011, the program achieved a major milestone with its fourth mission. A new biocapsule was launched on a suborbital flight, reaching an altitude of 135 km and returning safely to Earth.

The mission marked the debut of the Kavoshgar-C rocket, a significantly upgraded version of the Fateh-110 solid-fueled missile, weighing four times more than its predecessors, Nazeat-6H and Kavoshgar-B.

Iran continued refining its spaceflight capabilities with two additional suborbital missions on September 7, 2011, and September 8, 2012, both reaching an altitude of 120 km.

These missions demonstrated significant success, with the rapid retrieval of payloads and the successful transmission of biological data and onboard images.

Then, in 2013, Iran made history. In two groundbreaking missions, the country successfully launched a rhesus macaque—a species of Old World monkey—into space and brought it back safely.

On January 28, Pishgam, a three-year-old rhesus monkey, crossed the Kármán line, officially becoming the first Iranian mammal in space. With this, Iran joined an elite group, becoming the fifth nation to send a mammal into space and previously the sixth to send cold-blooded organisms.

Before Iran, only the two Cold War superpowers, along with France and China, had completed successful mammalian spaceflights, while Japan had limited its missions to non-mammalian species.

The 60 kg biocapsule that carried Pishgam was a technological feat in itself. Designed to accommodate a 2.5 to 4 kg primate, it provided optimal life-support conditions throughout the 20-minute flight.

The capsule was equipped with an advanced vibration-absorption system that neutralized 90 percent of unwanted energy, along with mechanisms to remove carbon dioxide and generate oxygen for up to five hours. Sensors continuously measured the monkey’s body temperature and heart rate, feeding real-time data to the central system, which then transmitted it back to Earth.

Beyond the biocapsule, every component of the mission performed flawlessly. The retrieval system, separation mechanisms, navigation controls, telemetry subsystems, thermal protection, rocket engine, launcher, and ground stations all functioned seamlessly, showcasing Iran’s growing expertise in human spaceflight preparation.

With these missions, Iran not only advanced its space biology research but also took one step closer to its ultimate goal: sending its first astronaut into space.

Race for human spaceflight

Iran’s bioastronautical achievements continued when on December 14, 2013, another rhesus monkey, Fargam, embarked on a historic space mission with nearly identical parameters to the previous flight.

This time, the launch was executed using the Kavoshgar-D rocket, a liquid-fueled derivative of the Shahab-1 ballistic missile. The mission lifted off from the circular launch pad of the Imam Khomeini Space Center in Semnan province, reinforcing Iran’s expanding space capabilities.

Facing skepticism and dismissive propaganda from Western media, Iran responded decisively –releasing full, uncut footage of both Pishgam and Fargam’s launches, their flights, and the successful parachute landings.

The transparency of these missions was a direct rebuttal to doubters, demonstrating the credibility of Iran’s space program on the world stage.

The bioastronautical program had a clear scientific focus: examining how spaceflight affects living organisms, studying aerodynamic heating, analyzing atmospheric reentry dynamics, and testing the efficiency of insulators and thermal shields in protecting biological payloads.

But its significance stretched beyond mere research. These missions laid the groundwork for Iran’s ultimate ambition—human spaceflight. By proving its ability to design, launch, and safely recover living beings from space, Iran took a decisive step toward sending astronauts into orbit.

Race for the fourth astronaut

Iran’s race to send astronauts into space initially depended on international partnerships. In 1990, Iran and the Soviet Union reached a preliminary agreement to send an Iranian astronaut to the Mir space station. However, the collapse of the USSR halted the plan before it could materialize.

By the mid-2000s, Iran had shifted its focus toward developing an indigenous human spaceflight program. The first unofficial reports surfaced around this time, and in August 2008, the head of the Iranian Space Agency (ISA) officially confirmed the effort.

Further details emerged when the Aerospace Research Institute (ARI) revealed that Iran’s bioastronautical program had actually begun in 2002, following a strategic agreement between the Ministries of Science and Defense to establish a joint space initiative.

Iran initially set ambitious targets. In both 2008 and 2010, officials announced plans to send astronauts into suborbital space – reaching an altitude of approximately 200 km – by 2019.

However, by 2016, the timeline was adjusted to 2025. Then came a temporary pause. The high costs of human spaceflight led to a government decision to prioritize satellite launches and commercial aviation development, delaying astronautic ambitions.

But as the 2020s began, a new chapter unfolded. Iran’s economy, having weathered years of sanctions and the US “maximum pressure” campaign, began stabilizing.

With renewed resources and determination, the human spaceflight program was revived.

Iran now targets 2029 for its first astronaut launch—setting the stage for the country to become only the fourth nation to send humans into space independently.

Iran’s human spaceflight program: From concept to reality

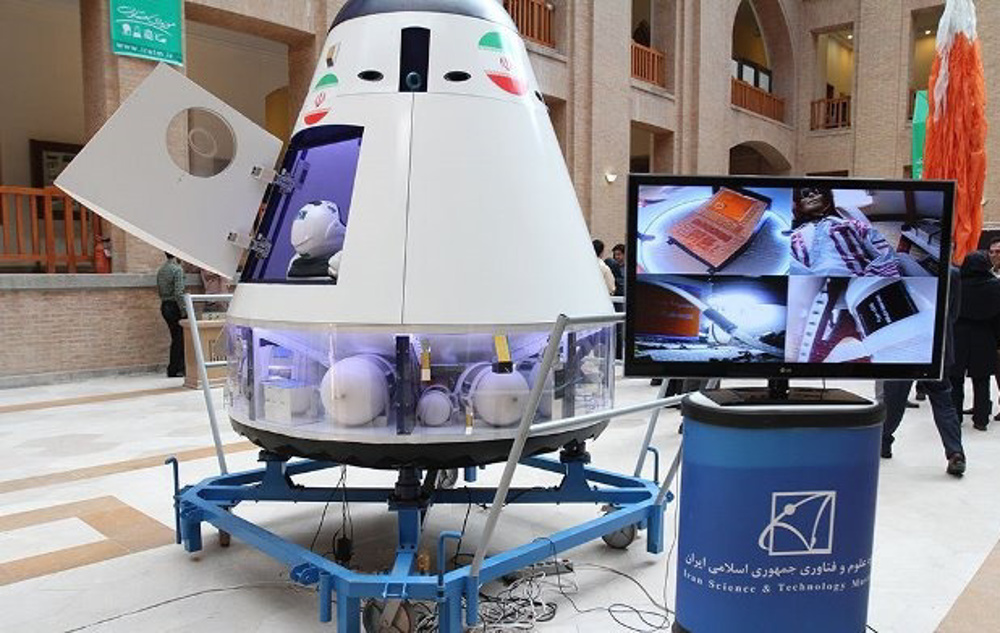

Iran’s journey toward human spaceflight took a tangible form in February 2015, when researchers and specialists from the Iranian Space Research Center showcased the E1 capsule –a mock-up of the country’s first manned spacecraft – at a technology exhibition.

This marked one of the first practical steps toward Iran’s goal of sending its own astronauts into space.

Following a temporary hiatus, the project regained momentum in January 2021, when the head of the Iranian Space Agency (ISA) announced that the Aerospace Research Institute (ARI) had completed the development of Iran’s first functional manned space capsule.

Initially expected to launch as early as June 2022, the capsule, named Kavous, finally took flight in December 2023 from the Imam Khomeini Space Center, propelled by the domestically built Salman rocket.

Designed by ARI, the Kavous capsule featured a conical shape with a 2-meter outer diameter and a height of 2.475 meters, providing space for a single astronaut.

With a mass of 500 kg, its dimensions surpassed those of all currently operational Iranian launch vehicles, including Safir, Qased (1.25 m), Zuljanah, and the second stage of Simorgh (1.5 m).

The noticeable size difference was evident when Kavous was mounted atop the narrower Salman carrier rocket. Given its weight—twice the orbital capacity of Simorgh—it was clear that the capsule was intended for suborbital flights within Iran’s current technological capabilities.

But this was only the beginning.

Next steps toward human spaceflight

According to ISA head Hassan Salarieh, the next stage in development is the construction of a 1.5-ton manned capsule by the end of 2025.

This indirectly signals the concurrent development of more powerful launch vehicles to accommodate such missions. Salarieh also confirmed that several additional test flights with increasingly complex and heavier capsules are planned before Iran attempts its first crewed mission.

The Supreme Space Council has laid out an ambitious three-year roadmap, prioritizing the development of advanced carrier rockets and a brand-new spaceport near Chabahar.

Central to this plan is the creation of Sarir, an upgraded version of Simorgh, designed to carry communication satellites into geostationary orbit (36,000 km) and lift a 4-ton payload into low Earth orbit (LEO).

Initial test flights carrying 1.5 tons of cargo are set for 2025 or 2026, with full operational capacity expected by 2027.

Parallel to Sarir, Iran is developing the even more powerful Soroush carrier rocket, capable of launching payloads of up to 15 tons. Expected to be operational by 2028, Soroush represents Iran’s gateway to full-fledged human spaceflight.

Both new launch vehicles will have the capability to propel a crewed capsule into suborbital and orbital missions—officially scheduled for 2029.

By meeting this target, Iran is poised to become the fourth nation to independently launch a human into space, following only the Soviet Union, the United States, and China. While other contenders – including the European Space Agency (ESA), Japan, and India –have long announced plans for human spaceflight, none have yet materialized their ambitions into an actual launch.

If Iran succeeds, it will solidify its place among the world’s elite spacefaring nations.

Participation shrinks at Israeli arms expo in wake of Gaza genocide: Report

Venezuela calls on UN to pressure US for Maduro’s immediate release

Hamas: Israel seeks to break Palestinian abductees’ will through abuse

Former UK ambassador released on bail after arrest in Epstein-linked probe

Hamas condemns Israel’s arson attack on mosque in West Bank, calls for mobilization

Trump's top general warns of Iran aggression risks: reports

VIDEO | US ambassador’s remarks on Israel’s expansion spark outrage

VIDEO | ‘Protect the Right to Protest’ rally held outside London court

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website