UK is to trial use of blood plasma from coronavirus survivors

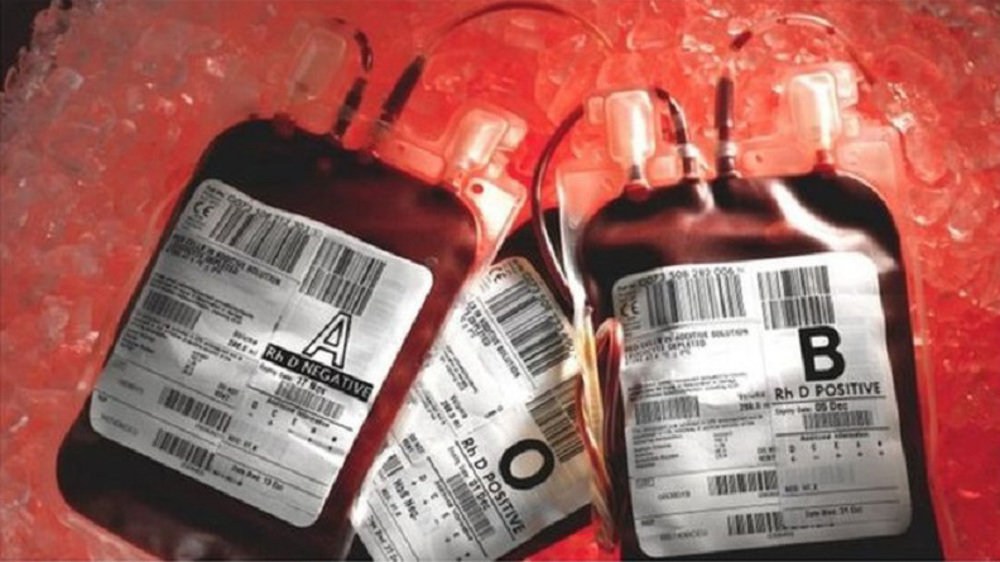

NHS Blood and Transplant (NHSBT) is asking people who have recovered from Covid-19 to donate their blood in the hope that the antibodies they have built up will help to clear the virus in others.

Trials are already underway in the US with more than 1,500 hospitals involved in a project to study this candidate therapy.

When the immune system detects COVID-19, it responds by creating antibodies, which attack the virus and accumulate in the plasma, the liquid portion of the blood.

A statement issued by NHSBT said, "We envisage that this will be initially used in trials as a possible treatment for Covid-19.

"If fully approved, the trials will investigate whether convalescent plasma transfusions could improve a Covid-19 patient's speed of recovery and chances of survival.

"All clinical trials have to follow a rigorous approval process to protect patients and to ensure robust results are generated. We are working closely with the government and all relevant bodies to move through the approvals process as quickly as possible."

Earlier this week University Hospital of Wales (UHW) in Cardiff announced its intention to trial the technology.

Professor Sir Robert Lechler, president of the Academy of Medical Sciences and executive director of King's Health Partners, which includes King's College London and three major London hospitals, is also hoping to set up another small-scale trial.

He wants to use plasma for seriously ill patients that have no other treatment options, while a larger national trial is getting under way.

He said, "I would be disappointed if we weren't able to see some patients given this form of therapy within a couple of weeks. Let's hope that the NHSBT national trial gets into gear really quickly."

He has criticized the UK for having been slow in testing the treatment.

"I think there are many aspects of this pandemic we'll look back on and say, I wonder why we didn't move a little bit faster. I think this could be one of those".

Scientists in the US have organised a nationwide project with about 600 patients treated in the three weeks since it began.

Prof. Michael Joyner, from the Mayo Clinic, is leading the work.

He said, "The thing we've learned in the first week of administration is that no major safety signals have emerged and administration of the product does not appear to be causing a whole lot of unanticipated side effects.

"There are anecdotal reports of oxygenation improving and other patient improvements. Those are certainly heartening, but they need to be rigorously evaluated."

He said the therapy was "rough and ready".

"There's a lot we don't understand about the plasma. We're going to learn more about what's in the plasma, the components, the antibody levels, and other factors that may be there as the weeks go on.

"But sometimes, as a physician, you just have to try to take a shot on goal when you have a shot."

This method, utilizing the blood of recovered patients, is nothing new in medicine. It was, in fact, used more than 100 years ago during the Spanish Flu epidemic, and more recently for Ebola and Sars.

To date, there have only been small studies into its efficacy, and there is a great deal of research that needs to be done to see how effective it will be against coronavirus.

According to the WHO, the experience in the past suggests that the empirical use of convalescent plasma can be a potentially useful treatment for COVID-19.

Though scientists say plasma won't be a magic bullet, with other options for treating coronavirus so limited, the hope is it could help until a vaccine is found.

Chinese Army calls on Japan to stop its ‘slanderous acts’ amid tensions

Iran’s mega water transfer and coastal industrial pivot

Majority of Americans oppose war on Venezuela

Missiles with strike radius beyond Persian Gulf length used in IRGC drill: Parl. speaker

US National Security Strategy is written for Israel: Tehran

VIDEO | Press TV's news headlines

How Lebanese Shiites welcomed Pope Leo XIV in a powerful display of national unity

Iran parliament speaker warns GCC states over repeated island claims

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website