How Lebanese Shiites welcomed Pope Leo XIV in a powerful display of national unity

By Lama Almakhour

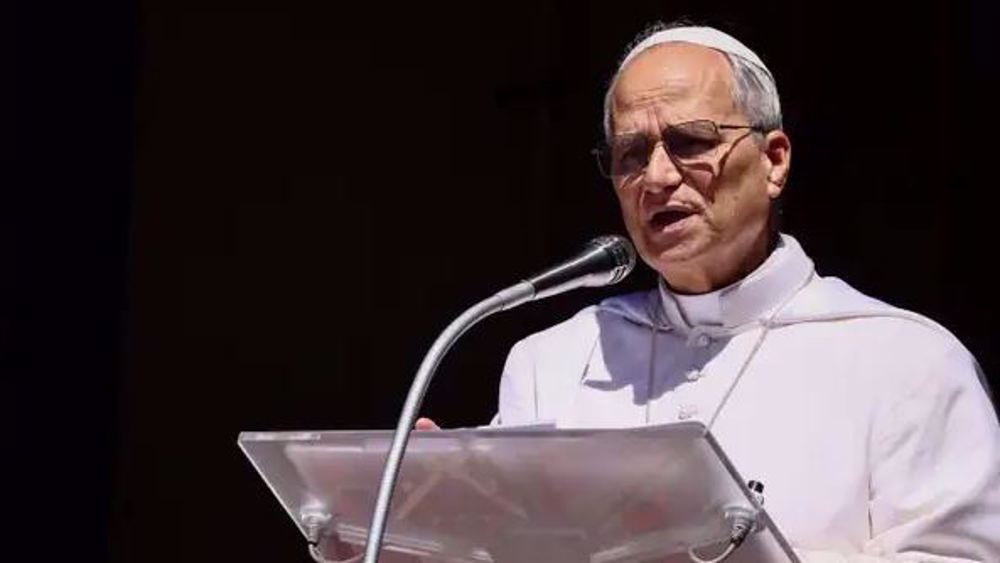

To the rhythm of traditional music and Lebanese folkloric dabke, the Land of the Cedar – as Lebanon is known – welcomed on Sunday Pope Leo XIV, the 267th head of the Catholic Church.

The reception of Robert Francis Prevost, who took the name Pope Leo XIV after becoming the head of the Roman Catholic Church in May last year, was more than just an official event in Lebanon. It was a heartfelt moment where one heart reached out to embrace another.

From the early morning hours, the streets overflowed with people of all ages and ideologies, carrying flags, pictures, and flowers, as if adorning their daily struggles with the last flicker of hope.

Faces glowed despite the simmering heat, and eyes were watchful as though awaiting a long-lost relative’s return. When his convoy finally appeared, applause rose like a unanimous heartbeat, supplications mixed with tears, and hands waved without ceasing.

Some were crying without fully understanding why – perhaps because moments of being truly heard are so rare in this country.

In the villages, people came to their balconies, hung decorations, and distributed bread and water to passersby, as if an unannounced holiday had descended upon them.

In the major city thoroughfares, the gathering transcended mere crowds. It was a profound spiritual fullness, a testament that Lebanon – wounded and bleeding though it may be – still holds the power to unite its people around a shared moment of hope.

They welcomed the Pope as one welcomes light into a home plunged in darkness, with tremendous gratitude and hearts wide open.

Pope’s visit to Lebanon, after Turkey, was a humanitarian and spiritual mission – to bestow blessings upon a country that, over the past two years, has endured relentless wars waged by the Israeli enemy, devastating everything from its stones and people to even its tree leaves.

One can’t help but wonder, how does the Pope begin his visit to a country where suburbs wake to the smell of smoke, and people in the South drift to sleep amid the echoes of bombardment?

This question echoes the pain of the Lebanese themselves. I imagined that upon arrival, he would tread softly through the rubble, choosing to see the human spirit before the ruins, hope before the devastation. Perhaps he would enter Lebanon through its most painful threshold, the door of its open wounds, to affirm that even beneath skies heavy with ash, light still finds a way.

Despite the religious weight of Pope Leo’s trip to Lebanon, the warm reception from the Resistance community and the Imam Mahdi Scouts became the defining moment, sparking immediate reactions from social media users.

— Press TV 🔻 (@PressTV) December 3, 2025

Follow Press TV on Telegram: https://t.co/LWoNSpkc2J pic.twitter.com/ZArk12o19X

Before reflecting on the reality of the Pope's itinerary, which unfolded far from the visions of this writer, visions that now seem destined for Plato’s ideal city, it is worth noting that the Municipality of Beirut and other areas had already begun a flurry of road and streetlight repairs

Ironically, these are the very roads where many Lebanese have died in traffic accidents.

How can a country, plunged in darkness for years, suddenly light up all its roads? How do potholes that swallow people's dreams turn into smooth sidewalks overnight?

The Lebanese watched the scene with a familiar bitterness. Everything had been beautified because the Pope was coming – lampposts lit, roads freshly paved, a level of order resembling that of dreamlike nations. It was as if the dormant state awakens only when the guest is distinguished, not when its own people are suffering.

The irony was sharp. The Pope had come to bear witness to the people’s pain, their struggles for the simplest of rights – light, safe roads, dignity – yet the visit nearly concealed the wound instead of exposing it.

And in the midst of this contradiction, the Lebanese stood in silence: how beautiful it is to see the country illuminated… and how heartbreaking that it shines first for someone other than its own people.

The scene was larger than a religious event and deeper than an official visit. In a country long divided by politics, identity, history, and even the struggle for bread and medicine, the Lebanese suddenly found themselves standing shoulder to shoulder as this revered Christian figure arrived.

It was expected that Christians would gather to welcome a spiritual symbol deeply rooted in their consciousness, but what was truly striking was the enthusiastic presence of Muslims, particularly from the Shiite community, whose level of participation is seen only when Lebanon remembers its capacity for unity.

Al-Mahdi Scouts and Al-Risalah Scouts, affiliated with Hezbollah and the Amal movement, stood along the roads organizing, applauding, and taking part with genuine sincerity. It was a moment that reminded everyone that sanctity is not the property of a single sect, but a sentiment shared by all who understand the worth of humanity.

For a few hours, Lebanon seemed to remember itself, a country that may disagree to the point of bleeding, but one that comes together instantly when touched by a glimmer of light, as though it had never been divided at all.

The motorcade of Pope Leo XIV passes through the streets of Beirut amid a warm welcome from both Christian and Muslim communities of Lebanon.

— PressTV Extra (@PresstvExtra) November 30, 2025

Follow: https://t.co/7Dg3b41PJ5 pic.twitter.com/8yrwNGdEfW

Upon his official arrival in Beirut, the Pope was welcomed by senior government officials, and the following day, he traveled to the Monastery of Saint Maroun in Annaya, where he prayed at the tomb of Saint Charbel Makhlouf, a gesture rich with spiritual symbolism and grace.

He then met with clergy, priests, nuns, and pastoral workers at the Shrine of Our Lady of Lebanon in Harissa, reaffirming the importance of coexistence and interfaith dialogue.

In the afternoon, he took part in an interfaith gathering at Martyrs’ Square in Beirut, where Christian, Muslim, Druze, and other religious leaders delivered messages of peace, and an olive tree was planted as a living symbol of hope.

Later, at the Maronite Patriarchate in Bkerké, he addressed the youth, urging them to become a generation of builders—unifiers who rise above division.

On the final day of his visit, he met with patients and visited a hospital in the Jal al-Dib area, before stopping in solemn silence at the Port of Beirut to pray for the souls of the victims of the 2020 explosion. He concluded his journey with a grand Mass on the Beirut waterfront, offering Lebanon words of hope and prayers for peace before bidding the country farewell.

In the collective memory of the people in the South, an old tale is often retold: that Christ once walked through its coastal villages, where people lived under the weight of fear and unspoken sorrow. They say he paused at the edge of one village and noticed a sick child cradled in the arms of a mother worn thin by sleeplessness.

He approached her softly, placed his hand on the child’s head, and murmured a word of peace. The moment his fingers brushed the little one, the child’s eyes fluttered open as though waking from a long, heavy dream; breath filled his chest again, and life surged back into the mother, who collapsed into tears.

Word of the miracle spread quickly. Villagers stepped out of their homes with tears, bread, and oil, seeking nothing more than the reassurance that heaven had not abandoned them.

Since that day, the story has passed from one generation to the next, a quiet testament that blessings still find their way to weary lands, and that the South, despite its many wounds, remains a place intimately known by light.

The Pope left Lebanon, yet his presence lingered in the air like an unfinished prayer. He carried with him the warmth of a blessing and left behind a quiet peace that settled into the hearts of Lebanese of all sects, as though his very hand had momentarily eased the weight pressing down on this exhausted country.

But even with that comfort, a subtle ache remained. The Pope, who knows the miracle of Christ, whose footsteps once touched the soil of the South, and who knows that the followers of Christ still live there, in the suburb, the South, and the Bekaa, where homes remain crushed beneath the remnants of Israeli aggression, could not reach them.

Perhaps security concerns rose higher than what could be overcome. Perhaps decisions and international powers – American and Israeli – proved stronger than the Pope’s quiet longing, that inner ache known only to God, to stand among those most wounded.

It is painful when peace is kept from the very places that need it most, painful when a visit remains unfinished, both in his heart and in the hearts of the Lebanese.

Yet despite everything, there was enough in his gestures, enough in the softness of his words, for people to feel he wished to be there. His absence from those regions was not neglect, but constraint.

And the constraints of this world, no matter how heavy, remain smaller than the sanctity of a pure intention he yearned, but was unable, to fulfill.

And I see in that nothing but the Israeli regime attempting to erase the trace of Christ in the South. In fact, in all corners of the earth.

And after all that has been recounted, it becomes clear that the brightest facet of this visit was the truth it quietly uncovered – a truth many had tried, for years, to blur or erase.

The Shiite community, so often and so unfairly portrayed as closed, extreme, or bound to foreign loyalties, revealed on this occasion an entirely different face: a community open at heart, gentle in faith, anchored in respect for all religions and spiritual figures, and fully present in the joys of the Lebanese before their sorrows.

They joined with music, with art, with disciplined organization, and with a sincerity that etched itself into the national scene. They showed that much of what is said about them is no more than rumors straining to become truth, and these rumors swept away the moment they stepped forward to welcome the Pope with genuine warmth.

They showed, too, that their loyalty belongs first and always to Lebanon – to its soil, its people, its collective moments – and that they remain children of this land, no matter how insistently some attempt to draft for them an identity other than their own.

Lama Almakhour is from Lebanon, who lost many members of her family in the recent Israeli aggression on her country, including her 5-year-old cousin and her mother. The article, originally written in Arabic, was translated into English by Roya Pour Bagher.

(The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of Press TV.)

Iran puts ‘Jam‑e Jam 1’ into orbit in milestone for national broadcasting

‘Colonial eradication of Palestine’: Iran condemns Israel’s West Bank annexation push

Thousands block Melbourne as Israeli president ends contentious Australia visit

Nearly 800 Lufthansa flights cancelled as pilots, cabin crew strike

Pezeshkian: US, Israel exploit Iran’s challenges without genuine concern

VIDEO | Press TV's news headlines

VIDEO | Chaos by design

Leader hails Iranians for disappointing enemies with multimillion rallies

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website