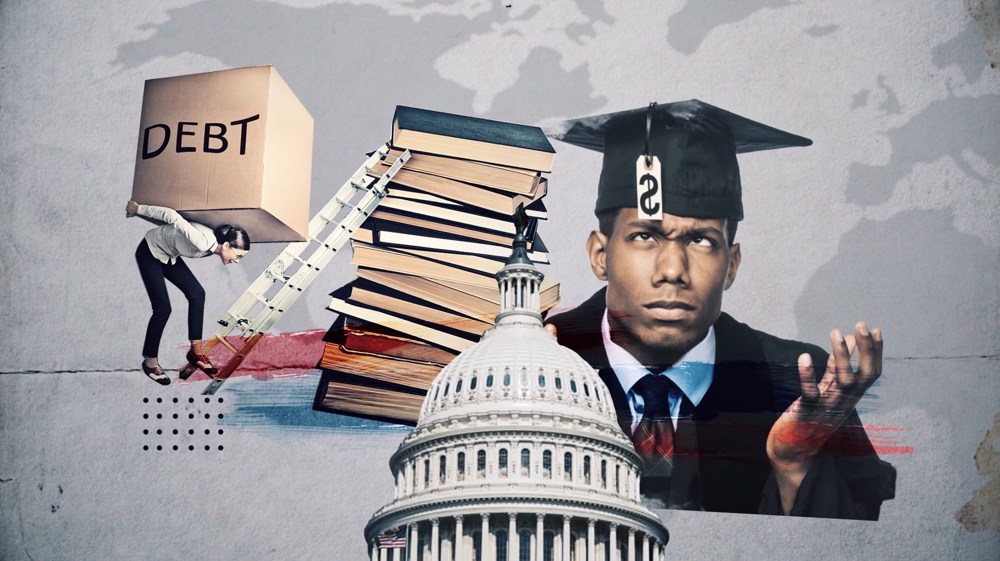

Explainer: How rising tuition and falling state support created US student loan crisis

By Ali Zeraatpisheh

Higher education financing in the US has undergone significant strain over the past several decades, and as a result, student loan debt has become a financial burden for millions of Americans.

By 2024, student loan debt reached about $1.8 trillion, held by nearly 45 million people, roughly one in seven adults. The average borrower owes more than $37,000. About 20 percent owe over $50,000, and more than 10 percent carry debts above $100,000.

Black graduates face the heaviest strain; their median debt is roughly $25,000 higher than that of white graduates, and nearly half are unable to make progress on repayment five years after finishing school.

Interest adds to the weight. Federal loans commonly charge 5 to 7 percent, and private loans often exceed 10 percent, allowing balances to grow even when borrowers make regular payments. Many borrowers now owe more than their original principal.

The crisis has deepened over time. Since 1980, tuition at public four-year universities has risen by more than 213 percent after inflation. State funding per student has fallen by about 16 percent.

Private colleges increased tuition by more than 150 percent. As costs rose, millions delayed major life decisions. Default rates remain close to 11 percent, and more than 8 million borrowers are in delinquency or distress.

This is not a short-term disruption. It reflects long-standing structural failures in the American higher-education and lending system.

How did the student loan crisis in US come to be?

The student debt crisis developed over several decades through policy choices that shifted the cost of higher education onto students. Until the mid-1970s, most states paid 60-70 percent of the cost of instruction at public universities.

Tuition was low, and borrowing was uncommon. By the early 1980s, state support began to fall. Between 1980 and 2000, per-student funding dropped by nearly 40 percent in several states. After the 2008 financial crash, many states cut more than 25 percent of their higher-education budgets within ten years.

Colleges filled the gap with tuition increases. As mentioned above, from 1980 to 2020, public university tuition and fees rose by more than 213 percent after inflation. Private nonprofit colleges increased tuition by about 150 percent over the same period.

Meanwhile, wages stagnated; the median hourly wage rose only about 9 percent between 1979 and 2020. Families no longer had income growth to offset rising costs.

The Pell Grant once softened this gap. Created in 1972 as the Basic Educational Opportunity Grant, it was intended to help low-income students avoid borrowing.

In the 1970s, the grant could cover more than 70 percent of the total cost of a public university, including tuition, room, and board. Its value eroded as tuition increased. By 2024, even the maximum Pell Grant will cover less than 30 percent of the cost of a four-year public institution.

Federal policy responded not by restoring grant support but by expanding loans. The Guaranteed Student Loan Program began in 1965. Unsubsidized Stafford Loans were introduced in 1992, allowing interest to accumulate while students were still enrolled. PLUS loans for parents and graduate students, created in 2006, opened the door to even larger borrowing.

In the 1990s and 2000s, universities became more financialized. Administrative expansion accelerated. For-profit colleges grew rapidly, enrolling students who often borrowed heavily and defaulted at high rates, frequently above 30 percent. By the early 2010s, borrowing had become routine: nearly two-thirds of graduating seniors had student loan debt, compared with less than one-third in 1990.

Who benefits from the crisis?

Several institutions gain from the student debt system while borrowers struggle. Federal and private loan servicers are among the main beneficiaries.

Companies such as Navient, Nelnet, and MOHELA collect large sums through servicing fees and interest management. Navient alone brought in more than $4 billion from federal servicing and private loan interest between 2010 and 2020. These firms profit from a complex repayment structure that allows interest, fees, and penalties to accumulate.

The federal government also gains revenue. For many years, federal student loans produced significant projected profits. The Congressional Budget Office estimated tens of billions in net revenue over multiple budget cycles, largely due to interest payments. Graduate PLUS loans, with no borrowing caps and interest rates often above 7 percent, remain especially profitable.

Universities have also benefited. As federal loan limits increased, colleges raised tuition, aware that students could borrow more. Many institutions grew administrative payrolls and funded non-instructional projects. Between 1993 and 2020, administrative spending at many universities rose at more than twice the pace of instructional spending.

These decisions allowed colleges to absorb expanded loan availability without improving affordability.

The for-profit college sector extracted even greater gains. At its peak in the early 2010s, the sector received nearly $30 billion in federal student aid each year. These schools enrolled large numbers of high-borrowing students who often had poor repayment outcomes.

Default rates at some for-profit institutions exceeded 30 percent, yet the institutions continued to receive federal funds until investigations forced partial shutdowns.

How did government policies make the crisis worse?

Federal and state policies widened the student debt crisis by protecting lenders, limiting borrower protections, and relying on loans instead of grants. A major turning point came in 1976, when Congress restricted the ability to discharge student loans in bankruptcy, even though less than 1 percent of federal borrowers filed for bankruptcy at the time.

Restrictions were tightened further in 1990, again in 1998, and then sharply in 2005, when the Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act made private student loans nearly impossible to discharge. Today, student loans are one of the few consumer debts, alongside taxes and child support, that cannot be cleared through bankruptcy.

Federal aid policy also shifted away from grants. In 1980, the maximum Pell Grant covered about 77 percent of the total cost of attending a public university. By 2024, it covered less than 28 percent, even as enrollment grew from 12.5 million in 1980 to nearly 20 million by the early 2010s.

During this period, federal borrowing expanded. Stafford Loan limits increased several times, allowing interest to accumulate during school, raising long-term repayment amounts. Graduate PLUS loans had interest rates above 7 percent and no borrowing caps, allowing graduate students to take on debts that often exceeded $100,000.

Weak oversight of for-profit colleges worsened the situation. By 2012, for-profit institutions enrolled approximately 2.4 million students and received nearly $33 billion annually in federal aid. Repayment outcomes were poor. Some institutions recorded three-year default rates above 40 percent, significantly higher than those of public universities, which averaged around 10%.

Loan servicing practices created additional harm. A 2017 federal audit found that more than 60 percent of borrowers in default had received incorrect or inadequate guidance from servicers.

Many were steered into forbearance instead of income-driven repayment. Forbearance allowed interest to grow and added thousands of dollars to balances. An estimated 5 million borrowers were affected by improper forbearance practices between 2010 and 2020.

State-level decisions also contributed. During the Great Recession, states cut higher-education budgets by an average of 23 percent between 2008 and 2013. Some cuts were far deeper: Arizona reduced per-student funding by over 50 percent, and Louisiana by nearly 40 percent.

Public universities responded by raising tuition. Between 2008 and 2018, average in-state tuition at public four-year institutions rose 37 percent after inflation.

How does the crisis affect people of the US in general?

The student debt crisis has direct and measurable effects on millions of Americans. As of 2024, more than 45 million people hold student loans. Around 7.5 million are at least 90 days delinquent or in default. Standard repayment schedules often last 21 years for undergraduate borrowers, while those with graduate debt commonly spend 25 to 30 years repaying.

These long timelines alter major life decisions. The median age of first-time homebuyers has reached 36, the highest ever recorded. Federal Reserve data show that student loan burdens reduced homeownership rates among young adults by at least six percentage points between 2005 and 2014.

Debt also depresses wealth. Borrowers aged 25 to 34 with student loans hold 75 percent lower median net worth compared with peers without debt. Among borrowers owing more than $50,000, nearly 30 percent have no retirement savings. For many, student debt functions as a long-term barrier to financial stability rather than a temporary cost of education.

Mental health outcomes are also affected. National surveys show that more than half of borrowers report anxiety tied to their loans, and about one in eight report suicidal thoughts related to debt stress. Consequences become more severe for those who default.

They face wage garnishment, tax refund seizures, and lasting damage to credit scores. In 2023 alone, more than 600,000 borrowers had wages garnished due to federal student loan defaults.

The burden falls unevenly. Black borrowers typically owe 95 percent of their original balance even 20 years after entering repayment, while white borrowers owe about 6 percent less than they originally borrowed after the same period. Women make up nearly two-thirds of all borrowers, and first-generation and low-income students carry disproportionate balances relative to their earnings.

The crisis has become a long-term social and economic strain. It reduces wealth, delays family formation, deepens racial and class divides, and imposes persistent psychological pressure on millions. Higher education, once viewed as a reliable path to stability, now traps many borrowers in decades of financial insecurity.

Fake deaths and celebs: Inside the farcical info war against Iran amid foreign-backed riots

Two MKO terrorists captured for roles in foreign-backed riots in Tehran

Trump source of ‘provocative, absurd’ messages on recent Iran riots: Envoy

‘French army fits in one football stadium’: Politician mocks troop deployment to Ukraine

At least 40 Palestinian journalists being held in Israeli prisons: Advocacy group

US delivers more F-35 jets to Israeli regime despite Gaza truce violations

Blair distances himself from Trump’s $1bn ‘Board of Peace’ fee

US Justice Department refuses probe into killing of Minneapolis mother

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website