Explainer: How can Iran help South Africa advance its civilian nuclear program?

By Ivan Kesic

Recent statements from South African authorities suggest that the country is open to Iran's assistance in advancing its civilian nuclear program, including the supply of nuclear fuel, construction of uranium enrichment facilities and development of new nuclear power plants.

Speaking to media persons on February 17, South Africa’s Minister of Mineral and Petroleum Resources, Gwede Mantashe, did not rule out involving Iran or Russia in the country’s nuclear expansion plans.

"We can't have a contract that says Iran or Russia must not bid; we can't have that condition," Mantashe stated. "If they present the best offer, we’ll consider any country."

The press queries to Mantashe, one of the South African government's leading proponents of expanding nuclear capacity, and other South African officials, followed recent remarks by the Donald Trump administration about bilateral cooperation between Iran and South Africa.

Washington has increased pressure on Pretoria after President Trump signed an executive order on February 7, accusing South Africa – without providing evidence – of "reinvigorating ties with Iran for commercial, military, and nuclear arrangements."

The order also criticized South Africa’s lawsuit against the Israeli regime at the International Court of Justice (ICJ), labeling it an "aggressive position" against a US ally, and warned of potential cuts to American foreign aid or assistance to South Africa.

Both President Cyril Ramaphosa’s office and South African Nuclear Energy Corporation (Necsa) CEO Loyiso Tyabashe denied claims of nuclear cooperation between the two countries, with Tyabashe emphasizing that no such agreement exists.

Mantashe, however, maintained that South Africa’s nuclear policy should not be dictated by foreign pressure, affirming that the door remains open to Iran for future collaboration.

South Africa has also reiterated that its international partnerships, including those with Iran and Russia, remain fully compliant with its commitments under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and the regulations of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

On which foreign technology does South Africa depend?

South Africa currently operates a single nuclear power plant with a capacity of 1,940 MW and has so far relied on French, American, and Chinese technology for its construction, maintenance, and fuel supply.

The Koeberg Nuclear Power Plant, the only operational nuclear facility on the African continent, was built between 1976 and 1984 by the French company Framatome (formerly Areva) during the apartheid era.

Owned and operated by Eskom, South Africa’s largest state-owned enterprise, Koeberg supplies more than 80 percent of the country's electricity. Framatome, France’s sole builder of conventional nuclear power plants, secured the construction contract after fierce competition with West Germany and a US-Dutch-Swiss consortium led by General Electric (GE).

Located along the Atlantic Ocean near the town of Melkbosstrand, 20 kilometers north of Cape Town, the plant consists of twin 970 MW pressurized water reactors (PWR), similar to those generating most of France’s electricity.

At the time of construction, Framatome was a licensee of the American company Westinghouse Electric Corporation, which designed the basic PWR units. Additionally, some reactor equipment was supplied directly from the United States by Combustion Engineering and Babcock & Wilcox.

The total cost of the plant was approximately $2 billion at the time (equivalent to about $7.5 billion today) and was expected to generate 7 percent of South Africa’s electricity.

The plant’s early years were plagued by numerous challenges, including rebel attacks, Western sanctions due to the apartheid regime’s escalating repression, and concerns over the military dimension of its nuclear program.

In response, France imposed a partial nuclear embargo, while the United States sanctioned exports of fuel and technology until South Africa acceded to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) in 1991.

Between 1993 and the early 2000s, Eskom collaborated with US-based Exelon and British Nuclear Fuels Limited (BNFL) on the Pebble Bed Modular Reactor (PBMR) project, which was intended to be built next to Koeberg but was ultimately canceled.

During this period, Koeberg’s two reactors experienced a series of technical difficulties, prompting Eskom to undertake significant technological upgrades. As part of these efforts, the utility replaced six steam generators, extending the reactors’ operational lifespan by 20 years.

The contract for the steam generator replacement was awarded to Framatome, despite objections and lawsuits from Westinghouse. Under a subcontract, the generators were manufactured in China by Shanghai Electric Nuclear Power Equipment Company (SENPEC).

Meanwhile, work on extending the lifetime of secondary turbine systems—boosting capacity by approximately 10 percent – was carried out by the American company Jacobs Engineering.

Who supplies South Africa with nuclear fuel?

Under a 1974 agreement, Eskom shipped natural uranium to the US Department of Energy for enrichment. However, four years later, the US Congress ruled that uranium enriched in the country could not be supplied to countries that did not permit International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) inspections.

This decision forced South Africa to seek alternative suppliers. By 1981, the country had purchased highly enriched uranium worth $250 million from France, as well as from Switzerland and Belgium, after receiving tacit approval from US officials.

The French contract required IAEA inspections at the Koeberg plant and mandated that all spent uranium produced by the reactors be sent abroad for reprocessing.

Western nations were generally reluctant to cooperate with apartheid-era South Africa, yet the country remained the world’s third-largest producer of uranium, a resource critical to numerous Western nuclear power plants.

During the 1970s and 1980s, as part of its military nuclear program, South Africa developed the unique Helikon vortex separation process and independently enriched uranium.

However, these capabilities were irreversibly dismantled when the country acceded to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) in 1991.

While South Africa initially intended to rebuild fuel production capacity as part of the Pebble Bed Modular Reactor (PBMR) project, although on a test scale, the project was ultimately abandoned.

Today, the country does not operate large-scale uranium enrichment facilities for domestic use or export and remains dependent on imported enriched uranium from the US and France.

In 1995, the US and South African governments signed the 25-year Agreement for Cooperation in Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Energy (commonly known as the 123 Agreement), which facilitated the use of US nuclear fuel in South African reactors.

The agreement, implemented in 1997, allowed for the transfer of nuclear materials under strict safeguards and security conditions.

Westinghouse became South Africa’s primary nuclear fuel supplier in the 21st century, initially securing a contract to deliver fuel in 2000, followed by additional reloads every four years. In 2009, the company was awarded a $30 million contract to supply the Koeberg power plant from 2011 to 2015.

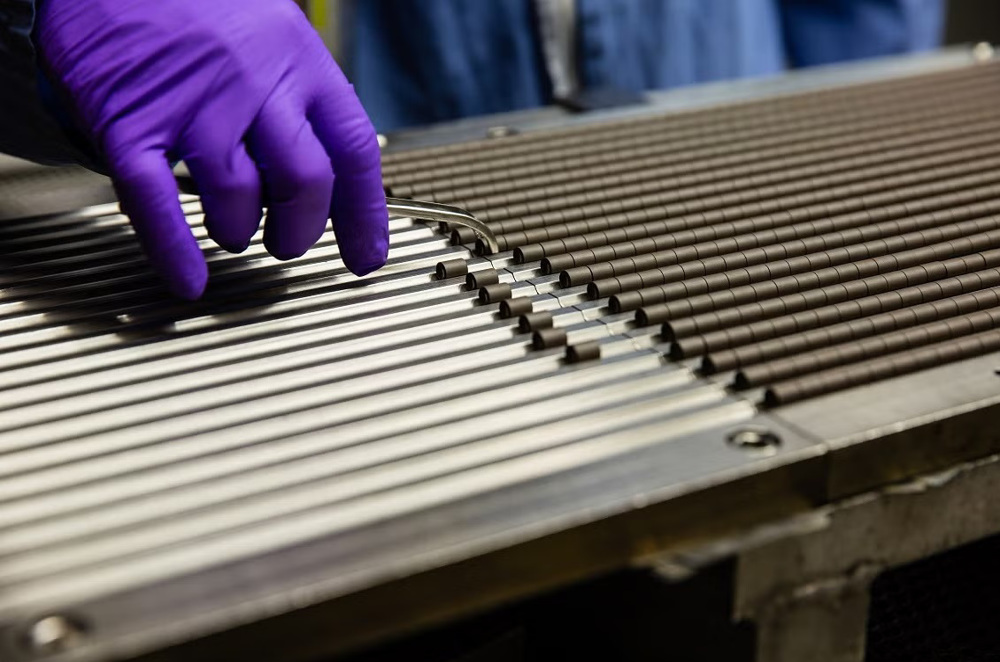

As part of this agreement, Westinghouse obtained a US Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) license to export fuel assembly components to its Swedish subsidiary, where they were assembled into fuel rods and shipped to South Africa under the terms of the 123 Agreement.

However, in late 2022, the US NRC suspended this export license, citing the expiration of the 123 Agreement. This left South Africa with limited nuclear fuel supplies and an uncertain future for the continued operation of Unit 1 at the Koeberg power plant.

Eskom has since clarified that French fuel supplied by Framatome is used for Unit 2 and that fuel supplies are secured until the end of 2026. Beyond that, the utility plans to seek a new supplier based on prevailing circumstances.

The US refusal to extend the license stems from Washington’s insistence on a new long-term agreement that would maintain South Africa’s reliance on imported nuclear fuel while preventing the country from reviving its independent uranium enrichment capabilities.

Meanwhile, since 2007, South Africa has outlined an ambitious nuclear energy program as a long-term strategic priority for energy security.

This plan includes reestablishing the full nuclear fuel cycle – conversion, enrichment, fuel fabrication, and reprocessing of spent fuel – as well as restarting the PBMR project.

South Africa maintains that these initiatives comply with IAEA regulations and will not only secure its own fuel supply but also position the country as a potential exporter of nuclear fuel in the future.

What are South Africa's future nuclear plans?

South Africa has long aimed to expand its civilian nuclear program, including the construction of new nuclear power plants and uranium enrichment facilities.

In 2007, Eskom approved plans for 20,000 MW of new capacity. However, subsequent revisions in 2010 reduced this target to 9,600 MW, and by 2020, it was further scaled down to 2,500 MW.

Under the original plans, traditional suppliers Framatome and Westinghouse were shortlisted, each offering to construct the full 20,000 MW capacity.

The French consortium proposed ten 1,600 MW EPR units, while the American consortium offered seventeen 1,134 MW AP1000 units. However, in late 2008, Eskom announced that it would not proceed with these bids due to financial constraints.

The 2010 Integrated Resources Plan (IRP) revised South Africa’s nuclear targets to 9,600 MW, with six 1,600 MW reactors expected to come online in 18-month intervals after an initial 13-year period.

Eskom subsequently sought more cost-effective alternatives to the French EPR and American AP1000 proposals, exploring potential partnerships with China, South Korea, and Russia.

This shift in strategy coincided with South Africa’s accession to the BRICS group in 2011, alongside Brazil, Russia, India, and China. During the early 2010s, several countries, including France, Russia, and China, signed agreements with South Africa expressing interest in constructing new nuclear power plants.

In 2013, Russia’s Rosatom proposed building the full 9,600 MW capacity with eight 1,115 MW VVER reactors by 2030, estimating $6 billion for the first two units, including waste management development and other collaborative projects.

That same year, Westinghouse signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with South Africa’s Sebata Group, an engineering firm, in preparation for potential AP1000 reactor projects.

In 2014, South Africa signed agreements with France for potential Generation III+ EPR reactors and with China for cost-effective CPR-1000 reactors, which were about half the price of their American and French counterparts.

Chinese industry officials later revealed they had also proposed CAP1400 reactors and expressed confidence in winning South Africa’s $80 billion nuclear bid, citing advantages in cost, reliability, and security.

Following cabinet approval in late 2015, South Africa’s Department of Energy issued a request for proposals for 9,600 MW of capacity by 2030. Five reactor vendors – Russia’s Rosatom, China’s SNPTC, South Korea’s KEPCO, France’s Framatome (Areva), and America’s Westinghouse – were invited to submit proposals detailing reactor design, localization potential, financing, and pricing.

However, in 2018, the South African government once again canceled the bid. A year later, it further reduced the planned nuclear capacity to 2,500 MW, shifting focus to the construction of two small modular nuclear reactors by 2030.

The National Energy Regulator of South Africa (NERSA) approved this revised plan in 2021, with officials announcing that the bidding process is expected to begin in the mid-2020s.

Additionally, South Africa plans to procure nuclear fuel, having previously estimated that a 9,600 MW capacity would require 465 metric tons of enriched uranium per year, while the revised 2,500 MW target would require approximately 120 metric tons annually.

The country also envisions establishing uranium conversion and enrichment plants during the 2020s, potentially through international partnerships or joint ventures.

How can Iran participate in South Africa's nuclear energy plans?

Given the current bilateral, international, and technological landscape, Iran has multiple avenues to engage with South Africa’s civilian nuclear program and help the country expand it.

Firstly, cooperation in nuclear fuel exports is a viable option. One of South Africa’s two current suppliers has refused to deliver new shipments, while the contract with the other is set to expire next year.

Eskom officials have publicly emphasized the importance of securing multiple suppliers to prevent power supply disruptions at the Koeberg power plant. This stance reduces competitive barriers for Iran.

Iran's stockpile of low-enriched uranium, which is compatible with Koeberg’s requirements, is estimated at around seven metric tons by the IAEA. With an annual production of several hundred metric tons, Iran is capable of meeting both its own needs and those of South Africa.

Historical data indicates that Koeberg’s two reactors consume approximately 30-40 metric tons of low-enriched uranium per year. The planned addition of two new reactors will slightly increase this demand.

With its advanced enrichment technology, Iran could also assist South Africa in developing uranium enrichment facilities – an area where many nuclear-capable states maintain a strategic monopoly.

On the other hand, a mutually beneficial bilateral agreement could grant Iran access to South Africa’s substantial uranium reserves. According to IAEA estimates, South Africa possesses 612,000 metric tons of uranium, the sixth-largest stockpile globally, significantly surpassing Iran’s 9,900 metric tons.

Such collaboration would position both nations as key players in the global nuclear fuel market, improving international competitiveness and driving more favorable pricing.

Furthermore, despite strong competition from six other major suppliers, Iran could also participate in South Africa’s tender for the construction of two new nuclear reactors.

While Iran currently operates only one nuclear power plant, Bushehr, built with Russian technology, it has been independently constructing the $20 billion Iran-Hormoz nuclear plant since last year.

This facility will feature four reactors with a total generating capacity of 5,000 MW.

The estimated investment for this project is two to three times lower than similar plants recently built by leading global manufacturers, demonstrating Iran’s competitive edge in nuclear construction costs.

A strong foundation for bilateral cooperation exists through both countries’ membership in the BRICS group, where their leaders have repeatedly underscored the importance of technological and energy collaboration.

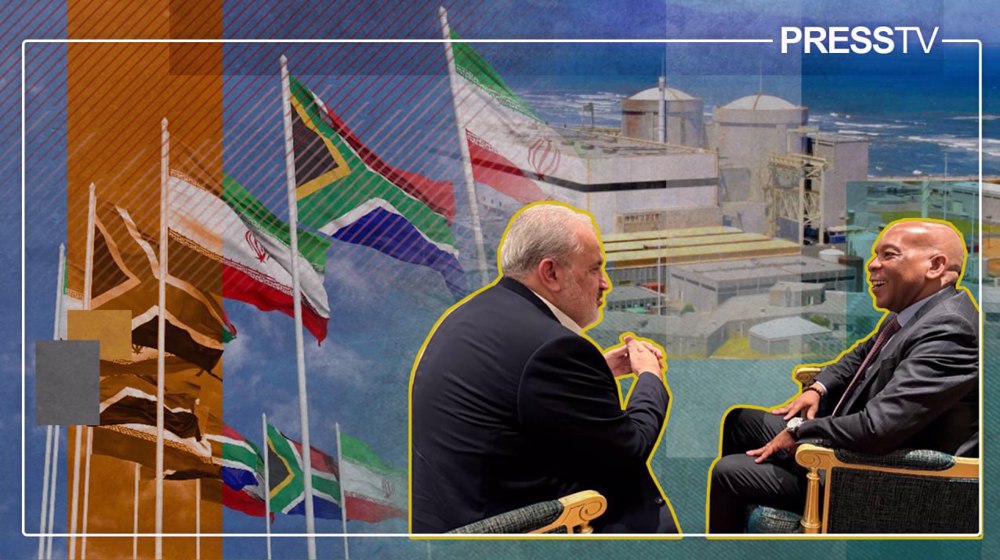

In September 2024, on the sidelines of the BRICS energy ministers' meeting in Moscow, Iranian Energy Minister Abbas Aliabadi and his South African counterpart, Gwede Mantashe, exchanged ideas on potential nuclear cooperation.

Highlighting Iran's expertise in the energy sector, Aliabadi said Iran is “ready to share these technical and specialized capacities with BRICS member countries, including South Africa.”

Both ministers emphasized expanding bilateral collaboration, particularly leveraging Iranian engineering expertise in South Africa’s electricity sector.

A year earlier, at the 15th BRICS Summit in Johannesburg, Iran announced an agreement with South Africa to develop and equip five refineries, signaling that energy cooperation between the two nations was already underway.

Netanyahu skipped Davos amid arrest fears: Reports

VIDEO | Press TV's news headlines

More Europeans see Trump as 'enemy' than 'friend': Survey

Ukraine war talks begin in UAE as Russia repeats Donbas demand

Iran slams UNHRC session as illegitimate, says no submission to foreign pressure

Six-month-old boy freezes to death in Gaza amid Israel's inhumane blockade

VIDEO | Protestors in South Africa slam US interference in other countries’ affairs

Israel runs smear campaign against Doctors Without Borders: Report

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website