Naṣir al-Din al-Ṭusi: The 13th century Iranian polymath who revived Islamic sciences

By Humaira Ahad

Naṣir al-Din al-Ṭusi, a renowned Iranian philosopher and astronomer, is credited with reviving Islamic sciences during one of the most turbulent periods in history.

Born at the dawn of a century marked by sweeping Mongol conquests across the Islamic world, Ṭusi – hailed as "the greatest scientist of medieval Islam" – played an instrumental role in preserving and revitalizing Islamic philosophy and theology.

According to official records, Tusi’s family originally came from Kashan, a historical city in central Iran, but he was born in the northeastern city of Tus on February 24, 1201.

The legendary Persian philosopher completed his initial education in Tus and Hamadan, studying the Quran, Hadith, jurisprudence, logic, philosophy, mathematics, medicine, and astronomy.

Later, he traveled to various cities in the Islamic world for advanced studies.

The scope of Ṭusi’s works spans an array of fields, including speculative theology, mathematics, astronomy, ethics, Sufism, and political thought.

According to the famous American scientist and historian George Sarton, the Iranian polymath was one of the greatest scientists of Islam. The renowned Muslim historian Ibn Khaldun asserted that most Muslim scholars were from Iran and noted that after Ibn al-Khatib, Fakhr al-Din al-Rāzi, and Naṣir al-Din al-Ṭusi, no other significant scholars emerged.

Tusi was honored with the title "Ustādh al-Bashar wa al-‘Aql al-Hādi ‘Ashar" (The Teacher of Humanity and the 11th Intellect) by later Islamic scholars.

Bar-Hebraeus, the 13th-century Syrian philosopher, regarded Tusi as “a man of vast learning in all the branches of philosophy.” Similarly, the Russian orientalist and scholar of Islam, Vladimir Ivanow, described the Iranian scientist as an "encyclopedist."

Tusi’s contribution to revival of Islamic civilization

Tusi lived in an era marked by harsh socio-political events across the Muslim world, a period often regarded as one of the worst in human history.

During this time, Mongol military power swept across vast swathes of the Islamic world. In a display of animosity towards Islam, they destroyed many noted centers of learning and massacred countless people.

The Iranian scholar played a crucial role in preserving Islamic literature by gathering scholars and promoting intellectual activities.

To protect scholars and the masses, Tusi decided to support the Mongol ruler Hulaku Khan. By securing an influential position in Hulaku’s court, he was able to mitigate some of the Mongol leader’s excesses against Muslims.

Tusi also used his influence to persuade Hulaku to allow him to safeguard the works of Muslim scholars and advance the cause of Islamic civilization.

His primary concern was the establishment of the Maragha Observatory, a prestigious research center dedicated to the study of Islamic sciences and philosophy.

This institution attracted scholars from around the world, both Muslim and non-Muslim, who came to study and conduct research.

Following the legacies of Jundi-Shapur in Persia (a pre-Islamic university) and Nizamiyya, founded by Nizam al-Mulk in Baghdad, the Maragha School became one of the most important madrasas in the Islamic world.

Praising Tusi’s contributions in securing Hulaku’s favor to preserve Islamic civilization, Arthur John Arberry, the British scholar of Islamic studies, wrote:

“That such a renaissance could take place at all, after the chaos and slaughter of the preceding years, was in large measure due to the collaboration of such as Naṣir al-Din Ṭusi and Shams al-Din Juvaini…”

Tusi’s literary contributions to Islamic civilization

Although much of Tusi’s life was spent among either the Assassins or the Mongols – amid wars, attacks, and retaliations, all of which were unfavorable conditions for study and research – he made remarkable contributions to intellectual development.

As a scholar of vast knowledge, he wrote approximately 150 books in Arabic and Persian. However, his most famous works were written in Persian.

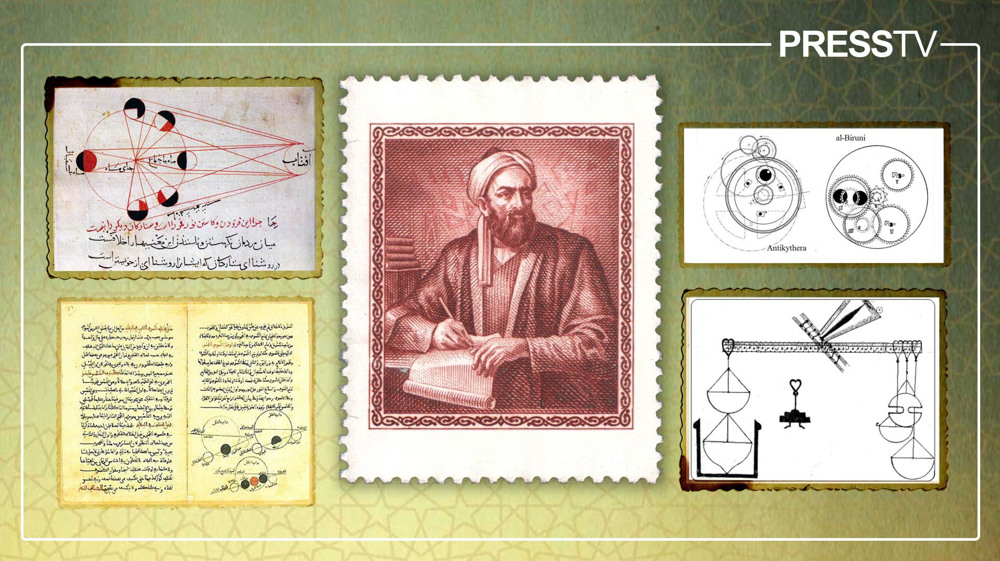

Tusi’s influence was most notable in astronomy, mathematics, philosophy, and theology.

His astronomical work, Zīj-i Ilkhānī (Ilkhan Tables), based on his research at the Maragha Observatory, is regarded as an accurate compilation of planetary movements.

His most influential book, Tadhkirah fi ‘Ilm al-Hayʿa (Treasury of Astronomy), introduced a geometric construction now known as the al-Ṭūsī couple.

Many historians of Islamic astronomy believe that the planetary models developed at Maragha later influenced Nicolaus Copernicus, the Polish astronomer, in his formulation of astronomical models.

To honor the Iranian astronomer’s contributions to science, NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration) named a lunar crater "Al-Tusi" in 1976.

According to Seyyed Hossein Nasr, a renowned scholar of Islam, Tusi’s major contribution to mathematics was in trigonometry, which he compiled as a distinct discipline for the first time. Nasr wrote in An Anthology of Philosophy in Persia:

“Trigonometry, for the first time, was compiled by him as a new discipline in its own right.”

Tusi also made significant contributions to Shia theology. Among his many theological works, Kitāb al-Tajrīd (The Book of Catharsis) is regarded as a key text in Shia theology.

Tusi’s illustrious legacy in philosophy

Tusi played a crucial role in spreading the influence of Ibn Sina (Avicenna) among later Islamic philosophers such as Mir Damad and Mulla Ṣadra.

His commentary on Ibn Sina’s Isharat wa al-Tanbihat (The Book of Directives and Remarks) was instrumental in promoting Avicennian philosophy.

Islamic scholars assert that Tusi’s work not only revived Ibn Sina’s thought but also produced a text that remains one of the primary sources for teaching Islamic philosophy in traditional circles to this day.

The commentary of Ṭusi is considered among the most significant works in Islamic philosophy, alongside only a few others.

Additionally, the Persian polymath wrote a renowned book on minerals, which included an intriguing theory on color, along with chapters on jewels and perfumes.

In 1273, Naṣir al-Din al-Ṭusi traveled to Baghdad in an effort to retrieve books that had been plundered during the Mongol invasions. However, he could not complete his mission and passed away on June 25, 1274, in the Iraqi capital.

As per his will, the great Iranian scientist was buried in the Al-Kāẓimayn Shrine, north of Baghdad. This shrine is home to the mausoleums of Imam Musa al-Kazim (AS), the seventh Shia Imam, and his grandson Imam al-Jawad (AS), the ninth Shia Imam.

Tusi instructed his students not to inscribe any political or scholarly title on his gravestone. Instead, he requested that a part of verse 18 from chapter 18 of the Quran be engraved:

“…and their dog [lies] stretching its forelegs at the threshold.”

Kabul rocked by explosions as Pakistan launches airstrikes

Iran Armed Forces warn US of severe consequences for any aggression

VIDEO | Iran, US move ‘closer to agreement’ after ‘serious, longest’ round of talks: FM

Israeli army chief privately warns of cost of new war with Iran: Report

IRGC official: US buildup, psychological tactics aim to 'swallow Iran again'

Iran’s three-man team captures triple gold at UWW ranking series in Tirana

Iranian academic sentenced to 4 years in prison in France for supporting Palestine

VIDEO | Press TV's news headlines

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website