India’s criminal laws overhaul prompts warning by activists

In the biggest criminal justice overhaul, India’s parliament has passed new laws with minimal debate after nearly 150 opposition lawmakers were suspended for protesting against the security breach in the lower house.

The parliament on Thursday rushed through passing new laws, alarming rights campaigners who say the new laws will give authorities too much power.

The new laws redefine the scope of “terrorism” offenses, and introduce new punishments for mob lynching and crimes against women.

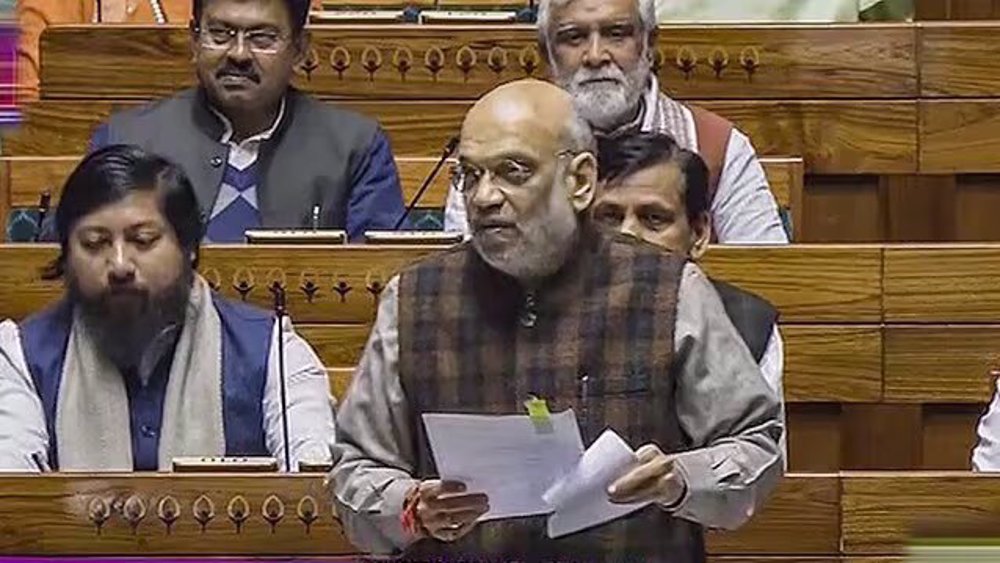

While moving three bills in the lower house in August, Home Minister Amit Shah said the old statutes had been designed to “strengthen colonial rule” and had outlived their purpose. “The motive of the three bills is not to give punishment but to give justice,” Shah told lawmakers on Thursday.

New provisions in the laws would impose death penalty on the perpetrators of mob lynching and rape of a minor. A minimum of 20 years will be given in cases of gang rape.

Community service provisions have been introduced for petty crimes to ease the chronic backlog in Indian courts, which have millions of pending cases.

The laws have also given increased power to police over the detention of suspects related to terrorism offenses. The definition of terrorism has been expanded to include acts that could threaten national sovereignty or “economic security.”

Many opposition leaders have dissented over these laws, citing concerns over limited time for consultation.

Amnesty International has said the new criminal justice framework would intensify a “targeted crackdown on freedom of expression in the country.”

The laws “dangerously broaden the definition of 'terrorism,' reintroduce sedition, retain the death penalty, and extend police custody,” Amnesty said.

The parliament also passed a telecom bill that will allow the government to temporarily take control of and suspend telecom services in the interest of national security. Campaigners say India already regularly uses internet shutdowns to manage unrest.

India's Penal Code and other statutes governing the police and courts were introduced in the 19th century, while the country was governed by the British monarchy.

US threatens Iraq with potential sanctions if Maliki returns as PM: Report

Iran and Russia’s quiet economic realignment

Iran Judiciary: EU resolution parrots counter-revolutionary claims

VIDEO | Aerial shots of floods in western France's Maine-et-Loire department

UK police usurped by Zionists

Baghaei to Press TV: Iran enters Geneva talks with ‘open mind and open eyes’

Warships can be sent to the seabed, Leader says in response to Trump’s threats

VIDEO | Press TV's news headlines

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website