'Painful and traumatic': Survivors recount horrors at US indigenous boarding schools

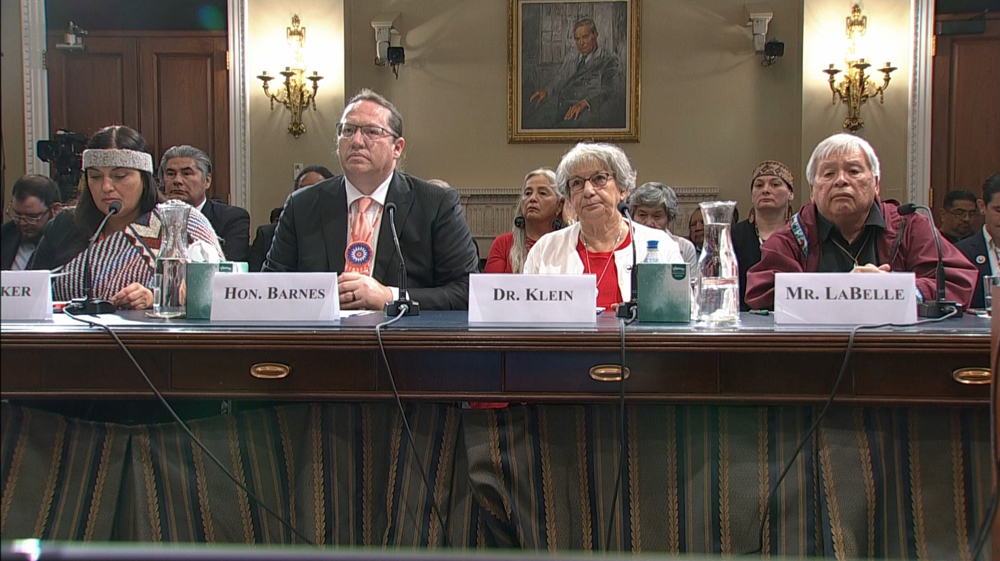

Sexual abuse and exploitation were common at Native American boarding schools, survivors told a US House subcommittee on Thursday while recounting their harrowing ordeals.

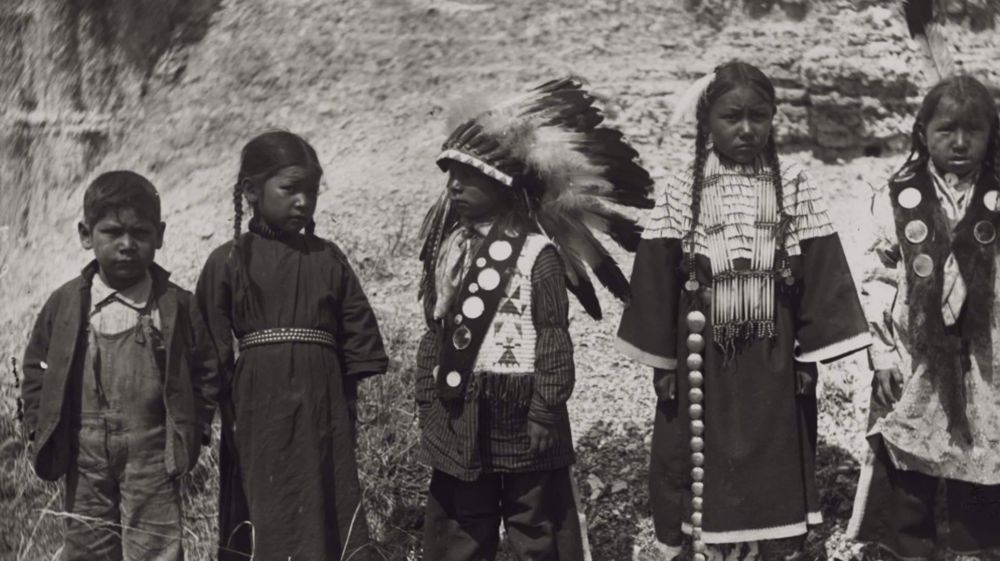

A first-of-its-kind federal study of Native American boarding schools, released on Wednesday, found that for over a century these schools sought to incorporate indigenous children into white society, which led to at least 500 students dying of brutal physical abuse.

The Interior Department study covers more than 400 schools that were established or supported by the US government in the early 19th century and continued functioning in some cases until the late 1960s.

Testifying before the House on Thursday, War Bonnet (76), one of the survivors, said he was beaten, starved, and stripped of his language and culture, calling the experience "very painful and traumatic,"

Bonnet was one of several Native American survivors of federally funded boarding schools to testify before the House subcommittee on a bill to create a ‘Truth and Healing Commission’ on the schools.

Bonnet and his nine siblings went to the same school, the Saint Francis Boarding School in South Dakota.

"It is hard to speak about it without making myself feel bad by bringing up these memories," he told the House subcommittee. “Corporal punishment was common. The priests would often get impatient and discipline us by hitting us with a leather strap or a willow stick.”

The notorious history of Native American boarding schools — where children were abused and prevented from speaking their languages— has long been suppressed by successive governments.

Many of these children never returned home, prompting many rights bodies to say that the number of student deaths could be in thousands or even tens of thousands.

Recounting the horror on Thursday, Bonnet said the priests at his school would “lock us out of the school during the cold weather”, and once he was given just bread and water to eat for ten days as punishment.

He further said that the children were forced to speak English and it became "difficult to speak with my parents in our Lakota language”, adding that the government and the churches “need to be held accountable for what happened at these schools.”

Jim Labelle, born in Fairbanks, Alaska, to a white father and an Inupiaq mother, also testified before the House subcommittee on Thursday, saying he had been waiting to “tell this story for my entire life”.

"We lost our ability to speak our language and do our traditional hunting, fishing, and gathering," he said the 75-year-old. "At the end of 10 years, I did not know who I was as a Native person.”

He said he learned American history, world history, math, science, and English, but was deprived of his own identity, culture, and language as an Inupiaq.

Labelle also recounted cruel punishment including being sprayed with icy water from a firehose.

"There was also sexual abuse," he said. "These schools were magnets for pedophiles."

A statement released along with the report on Wednesday said the school system had the "twin goals of cultural assimilation and territorial dispossession of Indigenous peoples through the forced removal and relocation of their children."

The Interior Department is in the process of sifting through thousands of boxes containing more than 98 million pages of records, according to reports.

A second volume of the report will cover burial sites as well as the federal government’s financial investment in the schools and the impact of the schools on indigenous communities, it said.

The department has so far identified at least 53 burial sites at or near boarding schools, with many unmarked graves.

Like the United States, Canada is also dealing with the legacy of abuse and neglect at its schools for indigenous children.

Thousands died at the schools, and many were subjected to physical and sexual abuse, according to an investigative commission that concluded the Canadian government engaged in "cultural genocide."

In March, a member of the Provisional Council of Métis Nation of Ontario (PCMNO) said Canada’s boarding schools were the shock troops of Canadian colonialism.

Speaking to Press TV’s Max Civili, Mitch Case said the reality is that Canada still hasn’t coped with its legacy as a colonial entity.

“Those schools – they were sort of the frontlines or the shock troops of colonialism,” Case said.

According to reports, over 150,000 Indian, Métis, and Inuit children were forced to attend 139 residential schools across Canada from the late 1800s to the 1990s, spending months or years isolated from their families.

The program aimed to isolate the indigenous children from the influence of their homes and culture and assimilate them into Canadian society by Christianizing them. But many of them were subjected to abuse, rape, and malnutrition.

Modi’s visit to Israeli Knesset faces opposition boycott

Israeli sniper in Chile could face criminal case over war crimes in Gaza

Young Iranian robotics specialists shine at IWISE Global Final 2026

Bangladesh poll result reflects public rejection of governance failures, not party loyalties: Analys

VIDEO | Iran holds 40th day memorial service for victims of US-orchestrated coup

Back to SAVAK days: Pahlavi monarchist violence surges against diaspora opponents

Russia threatens to deploy navy to protect vessels from ‘Western piracy’

Iranian Navy chief: Extra-regional fleets in West Asia 'unjustified'

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website