Iran, Russia rewiring global trade routes with Caspian link

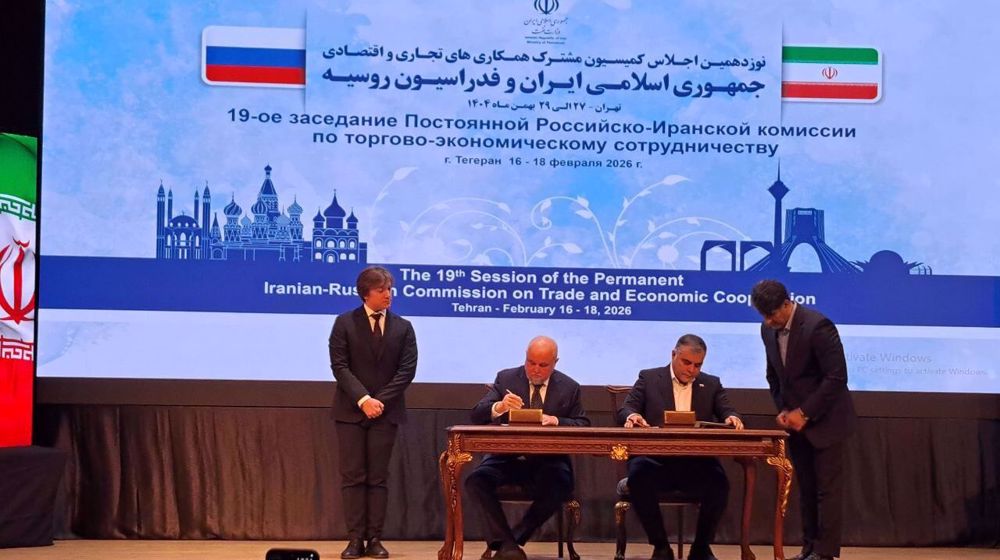

In Makhachkala on the Caspian Sea, Iranian and Russian transport officials agreed Friday to form a joint port and maritime consortium that will coordinate shipping, port management, and logistics between their ports.

The goal of the consortium is to move more goods, faster, between Russia and Iran and to connect that traffic with broader trade routes stretching to India, Central Asia, and the Persian Gulf.

The two sides plan to raise annual cargo volumes across the Caspian to more than five million tonnes in the coming years. The project builds on the International North–South Transport Corridor (INSTC), a 7,200-kilometer network linking the Indian Ocean to northern Europe through Iran and Russia.

Among the chain of ports along this corridor, Iran’s Caspian Port in Anzali Free Zone stands out as a critical node. With modern quays and sufficient depth despite the Caspian’s receding waters, it is viewed as a gateway linking Iran’s southern ports on the Persian Gulf to Russia’s transport network.

Western sanctions on Moscow have made this connection even more important, turning Iran into a logistical lifeline for Russian trade with Asia.

The new consortium marks a shift toward structured cooperation. It will bring together state and private port and shipping companies from both countries to coordinate tariffs, share facilities, and develop multimodal transport, moving goods seamlessly between sea, rail, and road.

Officials say the goal is to raise annual cargo volumes across the Caspian to more than five million tonnes, a significant jump from current levels.

This cooperation fits neatly within the bilateral cooperation treaty signed by Presidents Vladimir Putin and Masoud Pezeshkian in January 2025, which commits the two countries to expand collaboration in road, rail, air, and sea transport.

It also highlights their shared resolve to reduce reliance on routes vulnerable to political pressure from third countries as both face Western restrictions on trade and finance.

For Russia, the Caspian link provides access to warm-water routes and faster connections to India and West Asia without passing through Europe or the Suez Canal. For Iran, it offers transit revenues, investment in its northern ports, and a stronger role as a regional logistics hub.

The INSTC, which runs for some 7,200 kilometers through India, Iran, Azerbaijan, and Russia, could cut freight costs by up to 30 percent and reduce shipping times between Mumbai and Moscow from 40 days to around 20.

According to UN estimates, trade among the corridor’s member countries reached about $250 billion in 2021 and could double by 2030 if infrastructure and customs procedures improve.

Iran’s Seventh Development Plan sets a goal of increasing the country’s total transit capacity to 40 million tonnes by the end of the program, a target that depends heavily on the success of the North–South corridor.

The new consortium is a step toward that vision. The Ministry of Roads and Urban Development is pushing to expand container terminals at Caspian Port and build new logistics warehouses at Amirabad, another key Caspian facility.

Together with the rail link under construction between Rasht and Astara on the Azerbaijan border, these projects are designed to connect the Caspian ports directly to Iran’s national railway and, from there, to the Persian Gulf.

For Russia, the agreement is a pragmatic move. Since 2022, Western sanctions have upended its usual trade routes through the Black Sea and Baltic ports. By channeling cargo through the Caspian Sea and across Iranian territory, Moscow gains a more secure, sanctions-resistant pathway to southern markets.

Russian ports such as Astrakhan and Makhachkala already handle trade with northern Iran, but the new consortium promises a more coordinated framework for investment, shipping schedules, and customs procedures.

Behind the technical details lies a broader realignment in Eurasian logistics where the North–South corridor complements China’s Belt and Road Initiative. For many shippers, it offers a shorter, cheaper, and less congested route between South Asia and Europe.

For Iran, participation in such a transcontinental network helps attract foreign capital and counter the impact of US sanctions by turning geography into an economic advantage.

Both governments see logistics as an instrument of foreign policy as much as commerce. Russian officials have openly described the INSTC as a “strategic corridor” ensuring resilience under sanctions.

Iranian policymakers, for their part, view the Caspian ports as gateways to the Eurasian Economic Union, with which Tehran signed a free-trade agreement earlier this year.

At the Makhachkala meeting, officials also discussed harmonizing port tariffs, improving container handling, and developing training programs for maritime professionals.

They outlined plans to establish a joint legal structure for shipping operations, create a common association of port companies, and simplify permit issuance.

The next meeting, scheduled for later this year, will bring together public and private representatives to turn the framework into concrete projects.

If these plans advance, Iran could capture a larger share of regional transit flows and position itself as a vital connector between the Persian Gulf, the Caspian, and Russia’s inland transport network.

Bahraini police assaults crowds mourning loss of Ayatollah Khamenei

Iran posed no imminent threat to US: Pentagon tells Congress

Iran will hold no negotiations with US: Larijani

Despite Leader's martyrdom, Islamic Republic firmly in control and punishing the enemy

At least 31 killed in Israeli aggression on southern Lebanon after Hezbollah strikes

Iran writes to UN, warns about dire consequences for perpetrators following Leader's martyrdom

Hezbollah strikes occupied Haifa in retaliation for Leader's assassination

Ansarullah mourns Leader's martyrdom as 'great loss' caused by 'most wretched terrorists'

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website